Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit's performance before the TARP oversight panel yesterday in Washington must have Walter Wriston spinning in his grave.

So craven was Pandit that he renounced the bulk of Wriston's vision of money as an equivalent of information. Instead, Vik basically apologized for Citigroup ever attempting to be more than your good ole' neighborhood bank with a heart, only on a global basis.

He prostrated himself, verbally, in front of the panel, thanking them profusely for taxpayer funds which saved his bank.

When attacked for Citi's overseas presences and investments, Pandit claimed that Citigroup wasn't global, but American. Indeed, America's global bank.

How heartwarming. Patriotic, even.

Then Vik went on to assert that, after much rumination, he personally decided that Citi should be a bank. So he's been selling everything that isn't a bank. When asked how he felt about the "Volcker Rule," Pandit disingenuously claimed he was adhering to it by selling off little pieces of Citigroup. Of course, what Volcker really means is for banks like Citi, which enjoy FDIC deposit insurance protection, to stop risking solvency, and, thus, taxpayer funds on proprietary trading.

Either Pandit is so naive as to not understand this, or so clever as to believe his claims would fool the panel and viewers of his live act.

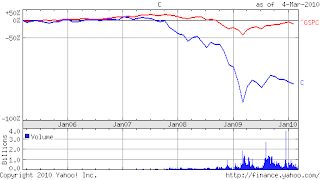

I wrote this spoof of an interview with Pandit 2 1/4 years ago, upon his being named CEO in December, 2007. The nearby price chart for Citigroup and the S&P500 Index for the past two years illustrates how much Citigroup has lost in value for its shareholders under Pandit.

I wrote this spoof of an interview with Pandit 2 1/4 years ago, upon his being named CEO in December, 2007. The nearby price chart for Citigroup and the S&P500 Index for the past two years illustrates how much Citigroup has lost in value for its shareholders under Pandit.The second chart provides a longer term perspective from five years back for the same series. About the best that could be said is that Pandit chose to accept the promotion from relative safety, running Citigroup's asset management unit, at an inauspicious time. Whether simply greedy, egotistical, or foolish, he walked into a maelstrom from which he, his bank and its private, non-governmental shareholders have yet to emerge.

There will be those, like someone who commented on one of my posts about Citigroup last year, who are short term opportunists, and have profited from the relative rebound of the company's equity since early 2009. But the risks associated with such a strategy were not low, and it appears that markets have taken back about a third of that temporary increase.

There will be those, like someone who commented on one of my posts about Citigroup last year, who are short term opportunists, and have profited from the relative rebound of the company's equity since early 2009. But the risks associated with such a strategy were not low, and it appears that markets have taken back about a third of that temporary increase.Even this morning, perennial Citigroup bullish analyst Dick Bove was, as usual, giving a glowing vision of the bank's future and firmly endorsing Citigroup as an investment.

I just can't get the image out of my mind of Pandit groveling before the government panel, clearly afraid of being accused of yet more misdeeds, made to suffer more penalties, perhaps even dismembered under the implementation of the Volcker Rule.

Is it realistic to bet on such a timid, defensive posture for Citigroup and its CEO for the coming years?