Wednesday's front-page column in the Wall Street Journal recounted Dell's recent missteps. Sad to say, much of what is related in the piece describes a simple failure of sensible marketing.

Wednesday's front-page column in the Wall Street Journal recounted Dell's recent missteps. Sad to say, much of what is related in the piece describes a simple failure of sensible marketing.As I've been reflecting on the piece, considering what perspective to apply to understand Dell's debacle, I think it is one of growth into ineptitude. Another story of a business model that successfully grew for quite some time, inadvertently sowing the seeds of its own destruction.

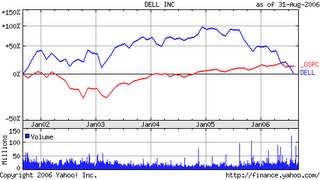

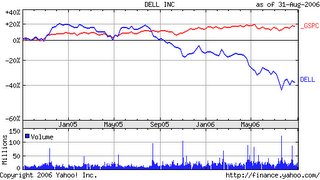

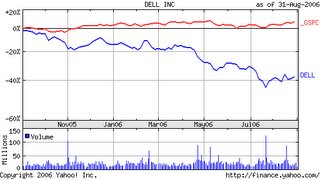

The charts at the left of this post illustrate the end of the company's era of consistently outperforming the S&P 500 index, with its performance worsening in the past 2 years. Over five years, it has been flat, while the S&P eked out a small gain. Over two years, Dell has fallen 40%, while the Index has risen almost 20%. In just the last 12 months, the Index has risen around 5%, while Dell has still declined about 40%.

The charts at the left of this post illustrate the end of the company's era of consistently outperforming the S&P 500 index, with its performance worsening in the past 2 years. Over five years, it has been flat, while the S&P eked out a small gain. Over two years, Dell has fallen 40%, while the Index has risen almost 20%. In just the last 12 months, the Index has risen around 5%, while Dell has still declined about 40%.In Dell's case, there seem to be three classic sources of that destruction of their successful business model.

First is an all-too typical case of what I refer to as "sand in the gears." Like Intel and Amazon, Dell must have begun rapidly assimilating the merely-average as employees. Seat-warmers who liked to boast, "yeah, I work at Dell," when that was a cool thing to say. However, witness what some of those customer management mavens did for Dell. They actually outsourced the retail phone order-taking function to temporary workers. Then refused to promote or "hire" any of them into the Dell workforce. The article states that turnover at these outsourced call centers reached 300%.

First is an all-too typical case of what I refer to as "sand in the gears." Like Intel and Amazon, Dell must have begun rapidly assimilating the merely-average as employees. Seat-warmers who liked to boast, "yeah, I work at Dell," when that was a cool thing to say. However, witness what some of those customer management mavens did for Dell. They actually outsourced the retail phone order-taking function to temporary workers. Then refused to promote or "hire" any of them into the Dell workforce. The article states that turnover at these outsourced call centers reached 300%.Let me see if I have this picture right. You take a group of people and tell them they aren't going to be "real" Dell employees, with Dell status and benefits level. Then you assign them the task of fielding calls from interested potential retail buyers. When they do a good job, you tell them they get nothing but "paid." And then Dell wondered why they lost ground in the retail segment.

That's a classic example of someone in charge being totally inept, and not caring a whit about the results of their ineptitude. Nor, apparently, for at least a few years, did their immediate and two-levels-up superiors.

Next, we have Dell's success in placing PCs into American homes become a factor in its own demise. By raising the bar with market penetration, the next buying decision for many families was approached differently than that of their first PC. Perhaps their needs changed, and grew. Or, perhaps they taught themselves that now, having successfully bought and used one PC, online or by phone, they knew enough to go to a locally sited big box retailer and buy "any" brand which satisfied their now-savvy technical/application needs and price points.

Lesson for marketing executives. When a market is immature, a brand can be worth quite a bit in terms of quelling customer post-sale cognitive dissonance. When the customer gets confident in his knowledge of the product, the rebuy decision won't be the same. And the customer may well value "brand" much less than when he was ignorant of the product.

So that seems to be another factor in Dell's lagging performance. Its marketing executives didn't keep their finger on the pulse of retail consumers, and, as a result, they missed important changes in that segment's buying behaviors. Score one for the bricks and mortar retailers, and the companies that elected to collaborate with them, like HP.

Finally, Dell has, I think, simply run out of road for its once-vaunted business model. This might be mostly a business development issue, rather than a marketing one. However, good marketing intelligence would have seen this coming, with the aforementioned changes in consumer buying behavior, as the changes were occurring, rather than two years later.

Would opening a chain of Dell stores have mattered? Maybe not. I've been looking around their website lately, and the cupboard's pretty bare for consumer products. In this case, I think one could fairly cast the issue as one of poor segment choice. The consumer segment seems to still be buying PCs, but Dell didn't really keep pace with features and price points, as its competitors did. They bet on the business segment, and it didn't provide sufficient growth and profitability to sustain Dell's formerly consistently superior total return performance.

It's not about exploding batteries, so much as just poor marketing in the swollen, mediocre ranks of Dell. And, thus, perhaps an unfixable problem, given the mature nature of the sector, and Dell's important and longstanding mistakes which have hurt it now for several years. It may well be the GM of the computer sector, going from dominant producer to an also-ran with product nobody really wants to buy anymore, and little room for a comeback.

Time will tell. And I don't think it will take all that much time, either.