It appears that investors are now in the grip of panic, amidst a healthily growing global economy. The source of that panic is the Federal Reserve. In particular, the new chairman, Ben Bernanke, has investors paralytic with fear that each new datum of global and/or US economic growth will cause Bernanke to ratchet up US interest rates even more, choking off said growth.

Further, economists seem now to be in two camps regarding the pace of the Fed’s tightening over the last two years or so. Some feel the Fed is still “catching up” with inflation, and has to tighten even more to become “neutral.” Others, however, feel that the Fed has already over-tightened, and needs to abate its increases before killing the US and global growth now in effect.

This week’s market index performance consisted of two lightly traded, insignificant days prior to the Fed meeting. On Wednesday, although up in the morning, the market, ended the day down, on the Fed’s rate increase news. Our portfolio, however, enjoyed a nearly .5 percentage point gain. Over the next two days, however, investors apparently became gloomier and gloomier, prompting a market sell-off which resulted in the loss of 2.4 percentage points of return. Growth stocks, including those in our portfolio, primarily energy, whose prices also sank, on fears of global growth abating, fell even more in these last two days. Considering the market’s reaction, it’s surprising our large-cap growth portfolio ended Friday down less than 1% more than the index for the week.

Even non-energy issues such as Apple and Whole Foods declined. Network Appliances fell by slightly more than 10%. BJ Services, EOG and Sunoco all declined between 6% and 10% for the week.

Seriously, did anything tangible really occur last week to drive long term values of companies like these down 10% in a few days? Doubtful. Perceived "spot" values amidst confused interpretations of Fed moves, yes.

As I look at the monthly portfolio returns for this year, one thought occurs to me. Over the past nine months, the major global economic story has been the rise of many commodity prices, including forms of energy, in the face of rising, legitimate demand levels. Nobody’s turning oil spigots off, blockading copper or titanium shipments, or refusing to sell or ship other basic industrial commodities.

The past few months have seen investors apparently uncertain with respect to what the Fed will do in reaction to US housing prices and, then, overall global demand. However, absent Fed actions to permanently dent growth and throw us back into a recession, it’s only a matter of time before energy and other growth-oriented issues once again become higher valued. Overall, it seems to me that the index’s 3.4% return under-represents the true strength of economic prospects. So long as the market is in one of those “there will never be growth again that is not punished by the Fed,” neither our growth-oriented portfolio, nor the market, is likely to move up sharply.

However, when investors come to realize that strong, low-inflation global growth does, indeed, exist, the market will move up. Remember last year's spring "soft patch?" The illusionary economic pause turned out not to be reall, and by June, the market took off on a tear. Our portfolio zoomed ahead, as it typically does during periods of realized healthy economic growth. Having seen this situation time and again, I suspect it will recur this summer.

Right now, a lot of mediocre analysts are trying to interpret and guess the behavior of some really intelligent, skilled people, i.e., the Fed Governors. Thus, we'll likely see a lot more senseless volatility and navel-gazing, until the global growth data and lack of inflationary effects of energy and other commodity prices are obvious. Some things don't seem to change.

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Friday, May 12, 2006

A Corporate Governance Thought Experiment: Part 1

Since November of last year, I have written 9 pieces on this blog concerning CEO compensation, and 8 concerning "corporate governance." There was a bit of overlap between them, so it's maybe a total of 15 pieces.

In some discussions with my partner and a few other friends recently, I've begun to form a new view of the overall notion of "corporate governance." Simply put, if the "corporation" is viewed, legally, as an ongoing "person," then perhaps what is needed is an explicit articulation of when that "person" needs to be put down. And, thus, how the company should be seen as dispersing its genetic material in order to continue to grow the value of its owners' capital investments.

When I put forth this notion to a consultant friend, she replied that 'there are already spinoffs.' However, I feel these have been historically done ad hoc, sometimes from outside pressure, less often from internal calculation. Or, even worse, under pressure from investment bankers, whose focus is always fees, and rarely, if ever, sustained superior performance of businesses to which they offer their "services." The answer isn't just "spinoffs," but, rather, how the entire notion of value preservation and transference, then growth, is perceived over time for a company's shareholders.

So, let me begin with a thought experiment, the first part of which I will post here. Suppose I had empirical evidence that demonstrated, based on many researched cases, that a specific pattern of revenue and profit growth, and consistently superior total return performance, which then flattened, was statistically unlikely to ever regain its former growth rate?

In such cases, would it not be sensible for a board to plan for the point at which the company begins to consciously cease to spend its resources on the parent's poor growth prospects, and, in a conscious, organized manner, deliberately identify, spinout and exploit various attractive businesses from the parent? Not in a reactive mode, but as part of a conscious plan to provide shareholders with the best chance of continued consistently superior returns from the seeds planted by the parent company.

There is a flip side to this challenge. That is, the large company which is now in a mature product/market, generating more cash than it can invest at similar returns in its existing businesses. My partner and I discussed the most obvious example of this situation- GM in the late 1980s, when it stumbled into buying EDS and Hughes. Both moves were, at the time, criticized as questionable, given the corporate charter of GM, and its existing business focus. Now, of course, it's laughable to think that they truly made those deals. But think of how much better off GM might be today, had it put as much energy into understanding and managing its automotive business as it did in making distracting acquisitions. Other examples which come to mind are the lockstep purchase of PBMs by major pharmaceutical companies in the last decade, only to see most of them unwound later. Who knows how much that distraction cost Merck, which now struggles just to maintain momentum in its main business?

To successfully manage such explicit transitions of value sources from a parent to a spinoff, of course, compensation plans and executive selections would need to reflect the evolution of the company's focus from self-growth, to propagating offspring ventures, while slowly winding down the parent.

Again, as a thought experiment, one can envision changing the staffing and compensation, so that revenue growth in the existing company becomes secondary to launching sustainable ventures which are not in the main area of the parent's business, as well as increasing profits. In essence, rather than have a management attempt to grow a mature business, perhaps shareholders are better served by an explicit exit strategy which rewards the 'right' behaviors, including, at some point, merging or selling the parent in what would have, by then, likely become a commodity business.

Such a strategy would not necessarily, or even likely, be possible for all consistently superior-performing companies. For instance, just now, amidst this week's various technology-related stories in the business media, I would constrast Microsoft, Intel, and Dell. Based upon their technological developments over the years, I believe Microsoft and Intel would be candidates for my concept of explicit evolution of a company to propagate worthwhile spinoffs. In fact, as I discussed with my partner last week, these companies, with their internal venture capital units in the late 1990s, probably were on the right track. They just looked in the wrong places- outside, rather than inside.

Dell, however, as an assembler and retailer, is unlikely to have much in the way of value to propagate beyond its own enterprise.

At this point, I'll end the first part of this idea, and continue it in a future post.

In some discussions with my partner and a few other friends recently, I've begun to form a new view of the overall notion of "corporate governance." Simply put, if the "corporation" is viewed, legally, as an ongoing "person," then perhaps what is needed is an explicit articulation of when that "person" needs to be put down. And, thus, how the company should be seen as dispersing its genetic material in order to continue to grow the value of its owners' capital investments.

When I put forth this notion to a consultant friend, she replied that 'there are already spinoffs.' However, I feel these have been historically done ad hoc, sometimes from outside pressure, less often from internal calculation. Or, even worse, under pressure from investment bankers, whose focus is always fees, and rarely, if ever, sustained superior performance of businesses to which they offer their "services." The answer isn't just "spinoffs," but, rather, how the entire notion of value preservation and transference, then growth, is perceived over time for a company's shareholders.

So, let me begin with a thought experiment, the first part of which I will post here. Suppose I had empirical evidence that demonstrated, based on many researched cases, that a specific pattern of revenue and profit growth, and consistently superior total return performance, which then flattened, was statistically unlikely to ever regain its former growth rate?

In such cases, would it not be sensible for a board to plan for the point at which the company begins to consciously cease to spend its resources on the parent's poor growth prospects, and, in a conscious, organized manner, deliberately identify, spinout and exploit various attractive businesses from the parent? Not in a reactive mode, but as part of a conscious plan to provide shareholders with the best chance of continued consistently superior returns from the seeds planted by the parent company.

There is a flip side to this challenge. That is, the large company which is now in a mature product/market, generating more cash than it can invest at similar returns in its existing businesses. My partner and I discussed the most obvious example of this situation- GM in the late 1980s, when it stumbled into buying EDS and Hughes. Both moves were, at the time, criticized as questionable, given the corporate charter of GM, and its existing business focus. Now, of course, it's laughable to think that they truly made those deals. But think of how much better off GM might be today, had it put as much energy into understanding and managing its automotive business as it did in making distracting acquisitions. Other examples which come to mind are the lockstep purchase of PBMs by major pharmaceutical companies in the last decade, only to see most of them unwound later. Who knows how much that distraction cost Merck, which now struggles just to maintain momentum in its main business?

To successfully manage such explicit transitions of value sources from a parent to a spinoff, of course, compensation plans and executive selections would need to reflect the evolution of the company's focus from self-growth, to propagating offspring ventures, while slowly winding down the parent.

Again, as a thought experiment, one can envision changing the staffing and compensation, so that revenue growth in the existing company becomes secondary to launching sustainable ventures which are not in the main area of the parent's business, as well as increasing profits. In essence, rather than have a management attempt to grow a mature business, perhaps shareholders are better served by an explicit exit strategy which rewards the 'right' behaviors, including, at some point, merging or selling the parent in what would have, by then, likely become a commodity business.

Such a strategy would not necessarily, or even likely, be possible for all consistently superior-performing companies. For instance, just now, amidst this week's various technology-related stories in the business media, I would constrast Microsoft, Intel, and Dell. Based upon their technological developments over the years, I believe Microsoft and Intel would be candidates for my concept of explicit evolution of a company to propagate worthwhile spinoffs. In fact, as I discussed with my partner last week, these companies, with their internal venture capital units in the late 1990s, probably were on the right track. They just looked in the wrong places- outside, rather than inside.

Dell, however, as an assembler and retailer, is unlikely to have much in the way of value to propagate beyond its own enterprise.

At this point, I'll end the first part of this idea, and continue it in a future post.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

Incomes Disparity: A Silver Lining

The Wall Street Journal featured an op-ed piece last week by two members of the President's Council of Economic Advisers, Edward Lazear and Katherine Baicker. Their article discussed recent job growth, wages growth, and per capita personal disposable income growth.

What was noteworthy is that the authors debunked the notion that most of the benefits of this growth are enjoyed by "the rich," and not "the poor." Rather, they found that college-educated wage-earners saw their earnings grow by 22% since 1980, while those of high-school drop-outs declined by 3% for the same period.

Thus, not unexpectedly, becoming wealthier, or earning more money, in our society is dependent upon education-based skills. This is no bad thing. I'd be much more worried about foreign competitive pressures if we learned that most wage growth was for only high school-graduated workers.

If anything, this should renew our government's focus on how to productively engage teachers' unions to help improve education, rather than simply siphon off more public tax dollars on teacher compensation. Failure to promote competent students to the college level, and beyond, is a real threat to our economic strength.

Rather than worry about the apparent disparity in wages among "classes," which is somewhat tautological, doesn't it make more sense to understand the reason for shrinking wages, and work to eliminate the cause- lack of adequate educational quality?

What was noteworthy is that the authors debunked the notion that most of the benefits of this growth are enjoyed by "the rich," and not "the poor." Rather, they found that college-educated wage-earners saw their earnings grow by 22% since 1980, while those of high-school drop-outs declined by 3% for the same period.

Thus, not unexpectedly, becoming wealthier, or earning more money, in our society is dependent upon education-based skills. This is no bad thing. I'd be much more worried about foreign competitive pressures if we learned that most wage growth was for only high school-graduated workers.

If anything, this should renew our government's focus on how to productively engage teachers' unions to help improve education, rather than simply siphon off more public tax dollars on teacher compensation. Failure to promote competent students to the college level, and beyond, is a real threat to our economic strength.

Rather than worry about the apparent disparity in wages among "classes," which is somewhat tautological, doesn't it make more sense to understand the reason for shrinking wages, and work to eliminate the cause- lack of adequate educational quality?

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

Microsoft vs. Google- Again

Yesterday afternoon, CNBC featured a brief debate between two analysts concerning Microsoft's current attempts to "catch" Google in the online advertising business.

One analyst echoed my own feelings and analysis. He said, nearly verbatim, what I discovered and wrote about in a post last fall; that once a technology firm has peaked, it's unlikely to have a successful second act in a new technology.

The other analyst's defense was that Microsoft has large margins in desktop software products, and rakes in huge revenue streams each quarter.

Actually, the two views are not at all mutually exclusive. Consider IBM. When it began to create the desktop PC market, it had large revenue streams and dominated the mainframe market. Yet, those attributes could not save it from a failure to dominate any part of the ensuing PC market in later years.

However, I think there is another reason Microsoft will no longer reward its shareholders with consistently superior total returns. Simply put, Bill Gates is too wealthy. He has no need to worry about financial performance of Microsoft anymore. Ironically, Microsoft now suffers, not from a CEO who owns to little of his firm's stock, but one who owns far too much of it.

Think about this. Gates has, by general estimation, somewhere between $24B and $25B. Let's suppose, for argument's sake, that all of it is in Microsoft stock. Even if Gates' strategy missteps were to cause a 90% drop in the value of the stock, which is far more than would be tolerated before his ouster, he would still be worth about $2.5B. Hardly poverty. I'm not even sure any human can behave differently, once his net worth is north of, say, $500MM.

The risk, then, to Microsoft, is that it now pursues blood feuds at the behest of Gates and Ballmer. Not really feeling the cost of failure, the two leaders of the firm seem to be going after Google "just because."

In contrast to this focus, CNBC aired an interview last week with another analyst who possessed a decidedly contrarian view. He instantly caught my attention.

This analyst maintains that Microsoft made a serious blunder in entering browsers to begin with, and has doubled up on the mistake by now pursuing online advertising. He pointed out that it has had a virtually monopoly in desktop operating systems, but has left that product class poorly served. An example of his contention was the one I mentioned recently here, of my partner failing to get IE7.0 to install on his XP-run laptop. Thus, fissures have opened within the desktop world for all sorts of products that fix Microsoft operating system failings and omissions. Surely, Microsoft could have been creating smaller, additional revenue streams with subsequent version enhancements all these years, while building an ever more solid position in the desktop OS world.

Well, that ship has sailed. And, instead, Microsoft shareholders are buckled in for a wild ride, as the firm's leading billionaire, and his henchman, go tilting after the Google windmills.

As SpongeBob would say, "Good luck with that!"

One analyst echoed my own feelings and analysis. He said, nearly verbatim, what I discovered and wrote about in a post last fall; that once a technology firm has peaked, it's unlikely to have a successful second act in a new technology.

The other analyst's defense was that Microsoft has large margins in desktop software products, and rakes in huge revenue streams each quarter.

Actually, the two views are not at all mutually exclusive. Consider IBM. When it began to create the desktop PC market, it had large revenue streams and dominated the mainframe market. Yet, those attributes could not save it from a failure to dominate any part of the ensuing PC market in later years.

However, I think there is another reason Microsoft will no longer reward its shareholders with consistently superior total returns. Simply put, Bill Gates is too wealthy. He has no need to worry about financial performance of Microsoft anymore. Ironically, Microsoft now suffers, not from a CEO who owns to little of his firm's stock, but one who owns far too much of it.

Think about this. Gates has, by general estimation, somewhere between $24B and $25B. Let's suppose, for argument's sake, that all of it is in Microsoft stock. Even if Gates' strategy missteps were to cause a 90% drop in the value of the stock, which is far more than would be tolerated before his ouster, he would still be worth about $2.5B. Hardly poverty. I'm not even sure any human can behave differently, once his net worth is north of, say, $500MM.

The risk, then, to Microsoft, is that it now pursues blood feuds at the behest of Gates and Ballmer. Not really feeling the cost of failure, the two leaders of the firm seem to be going after Google "just because."

In contrast to this focus, CNBC aired an interview last week with another analyst who possessed a decidedly contrarian view. He instantly caught my attention.

This analyst maintains that Microsoft made a serious blunder in entering browsers to begin with, and has doubled up on the mistake by now pursuing online advertising. He pointed out that it has had a virtually monopoly in desktop operating systems, but has left that product class poorly served. An example of his contention was the one I mentioned recently here, of my partner failing to get IE7.0 to install on his XP-run laptop. Thus, fissures have opened within the desktop world for all sorts of products that fix Microsoft operating system failings and omissions. Surely, Microsoft could have been creating smaller, additional revenue streams with subsequent version enhancements all these years, while building an ever more solid position in the desktop OS world.

Well, that ship has sailed. And, instead, Microsoft shareholders are buckled in for a wild ride, as the firm's leading billionaire, and his henchman, go tilting after the Google windmills.

As SpongeBob would say, "Good luck with that!"

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

Wachovia's Acquisition

Wachovia Bank announced its intention to acquire Golden West Financial. It will be a non-hostile takeover.

The shareholders of GDW should be happy with their premium. By contrast, Wachovia's shares fell on the news.

Per my prior post on this topic, I wonder what long-term value will be created by this further concentration of financial businesses into an even larger utility.

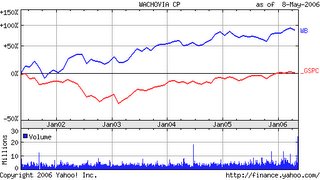

As the five year chart of Wachovia's stock price demonstrates, it has, indeed, outperformed the S&P over the time period, although most of that outperformance was in the early years of the period. This causes me to think that Wachovia may, indeed, now begin to see its total return performance wind down to that of the other three large financial utilities about which I wrote recently: Chase, Citigroup and BofA.

One has to wonder what, other than money, Wachovia brings to the Golden West operation? Decentralized control of the new entity seems almost too much to ask, for such a large acquisition. Of course, centralizing more control of the new subsidiary is bound to cause some disruptions in the performance which evidently so captivated Wachovia's leadership.

Either way, it looks like there's now room for some new, more nimble mortgage lenders in the West Coast market.

Monday, May 08, 2006

"....Because the Light Is Better Over Here......"

There was a very nicely done, extended video obituary of Lou Rukeyser on CNBC last Friday night.

True to form, Maria Bartiromo added only some pensive looks and a few head bobs. No original thoughts. Rather, she seemed engaged in playing traffic cop among people like Tyler Matheson, Bill Griffiths, and selected guests. Then again, this obviated the need for a teleprompter, so she didn't squint or lean forward quite nearly so much as she usually does on camera.

I don't wish to dwell on Maria. Rather, I use her to make a point. It seems that CNBC, and most financial or business television, focus on the the stock exchange. Bartiromo's apparent claim to fame, judging from her CNBC bio, is that she was the first to report live from the floor of the exchange.

Big deal.

This so misleads people regarding "where" the action really happens. It's not on the floor of the exchange. You may as well put a camera on an Amazon warehouse to watch them fill orders off the shelf. Or maybe a Netflix distribution center.

The real action in the markets happens in the offices and at the computers of money management institutions around the globe. It's not sexy, and it's not very "active," from a television point of view.

So, the title of this piece suggests a comparison with the old joke about where to look for a lost quarter. Rather than focus on where the financial news is actually "made", CNBC chooses, instead, to cover what "looks" more like "news." Lots of people shouting and running. Earpiece tightly pressed in by the reporter, looking up at some apparent big screen, then around at the hustle and bustle. Boy, something must be going on there.

If that's true, why did John Thain go to so much trouble to get acquired by.....oops...sorry...buy Archipelago Holdings? All the news you need to know about the markets is on a realtime screen feed of your choosing, for free. Do you really think those people scurrying around the floor of the Exchange are the movers and shakers of the market?

Nope. They are the financial market's equivalent of the driver who brings the Domino pizza to your door. Better paid, but not much different functionally- the last step in an order taking/fulfillment process. And, yes, do check under the box cover to see if you're getting the right pizza...er....order fill.

So, next time you see a breathless reporter or anchor for CNBC, or CNN, etc, on the floor of the NYSE, stop and think about what is really going on in the background. And why you are interested in what the order-takers "think" about the market.

True to form, Maria Bartiromo added only some pensive looks and a few head bobs. No original thoughts. Rather, she seemed engaged in playing traffic cop among people like Tyler Matheson, Bill Griffiths, and selected guests. Then again, this obviated the need for a teleprompter, so she didn't squint or lean forward quite nearly so much as she usually does on camera.

I don't wish to dwell on Maria. Rather, I use her to make a point. It seems that CNBC, and most financial or business television, focus on the the stock exchange. Bartiromo's apparent claim to fame, judging from her CNBC bio, is that she was the first to report live from the floor of the exchange.

Big deal.

This so misleads people regarding "where" the action really happens. It's not on the floor of the exchange. You may as well put a camera on an Amazon warehouse to watch them fill orders off the shelf. Or maybe a Netflix distribution center.

The real action in the markets happens in the offices and at the computers of money management institutions around the globe. It's not sexy, and it's not very "active," from a television point of view.

So, the title of this piece suggests a comparison with the old joke about where to look for a lost quarter. Rather than focus on where the financial news is actually "made", CNBC chooses, instead, to cover what "looks" more like "news." Lots of people shouting and running. Earpiece tightly pressed in by the reporter, looking up at some apparent big screen, then around at the hustle and bustle. Boy, something must be going on there.

If that's true, why did John Thain go to so much trouble to get acquired by.....oops...sorry...buy Archipelago Holdings? All the news you need to know about the markets is on a realtime screen feed of your choosing, for free. Do you really think those people scurrying around the floor of the Exchange are the movers and shakers of the market?

Nope. They are the financial market's equivalent of the driver who brings the Domino pizza to your door. Better paid, but not much different functionally- the last step in an order taking/fulfillment process. And, yes, do check under the box cover to see if you're getting the right pizza...er....order fill.

So, next time you see a breathless reporter or anchor for CNBC, or CNN, etc, on the floor of the NYSE, stop and think about what is really going on in the background. And why you are interested in what the order-takers "think" about the market.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Gates & Microsoft In the News Again

It was a big week for Microsoft. Well, a big ten days, if you count the 11% selloff of two Fridays ago, when Microsoft reported larger than expected expenses, sending the stock's price plunging.

But this week saw two different, but, to my mind, reinforcing glimpses of a Microsoft grown overly-large and in trouble.

The first was a Wall Street Journal piece on Thursday, detailing the company's development of its "adCenter" service. This is Microsoft's response to Google's AdSense program. The WSJ piece contained this quote from Microsoft's Senior Director Joe Doran, 'Microsoft's efforts in online advertising are equivalent to building a whole new company.' This passages was paraphrased in the WSJ, and the italics are mine. Doran was further quoted, "I feel confident we are making the right investment decisions." This is, by the way, part of the $2B investment which the article notes Microsoft will spend on development next year. The so called "far more than expected," according to analysts, which sent the stock plummeting two Friday's ago.

As I wrote last fall in a post about Gates and Steve Jobs, and their respective business efforts, I believe this entire approach by Gates and Microsoft will fail to reignite the firm's total return performance. The reason is the same as I articulated in the prior post, even considering that now the subject is a clone of Google's AdSense.

My friend S, the consultant to whom I referred in my recent Intel posts, and I discussed this point. She expressed disbelief that anything could really be different if Microsoft spent the same money on a separately-organized and funded effort that was physically and organizationally removed from the parent. I remain convinced it would.

How many of us have not worked in very large corporations, and watched how cultural forces mangle, compromise and choke the life out of new initiatives?

Microsoft is primarily a desktop software company. That is where it has made the bulk of its money, and produced the bulk of its deliverables. Trying to suddenly graft "online" onto it is a mistake.

As an example of this, my partner regaled me yesterday with his tale of attempting to install the new MS Internet Explorer browser version on his computer. It wasn't pretty. Firefox installed in a few minutes, flawlessly. He told me IE took 40 minutes, with multiple reboots every time the program failed to mesh with its own firm's registry software. Can it get much more pathetic than that? Microsoft controls both the OS and the browser, to the consternation of the regulatory authorities, and still can't get them to work together seamlessly.

This type of legacy penalty is part of the reason why I see Microsoft falling way short of its objectives of stopping Google's domination of the online advertising business. The other, of course, is simply the stifling culture of a behemoth now grown large and less nimble.

Complementing this story is what I saw in the brief clips of Bill Gates being interviewed by Donnie Deutsch on Friday. Suffice to say, Bill doesn't inspire much fear or confidence in Microsoft's new objective of taking on Google. When asked what he'd tell the Google execs, were they in the audience, Bill replied, smiling nervously, "we're going to keep them honest."

Wow, talk about killer goals. He's going to 'keep 'em honest.' I'll bet Serge is quaking in his boots after that warning!

Bill went on to babble about "having fun," how all the researchers in the Microsoft labs are "having fun" working on online and advertising services. That Bill and the whole firm are still "having fun." Nary a single word about profit, growth, or total returns.

Not being a Microsoft shareholder, this doesn't really bother me. But if I were, "having fun" would not be the main objective I'd be wanting to hear from Chairman Bill. I think his billions have finally dulled his instincts for profitable competition. Now, it looks like he's just using public funding to boost his ego and settle competitive business grudges.

But this week saw two different, but, to my mind, reinforcing glimpses of a Microsoft grown overly-large and in trouble.

The first was a Wall Street Journal piece on Thursday, detailing the company's development of its "adCenter" service. This is Microsoft's response to Google's AdSense program. The WSJ piece contained this quote from Microsoft's Senior Director Joe Doran, 'Microsoft's efforts in online advertising are equivalent to building a whole new company.' This passages was paraphrased in the WSJ, and the italics are mine. Doran was further quoted, "I feel confident we are making the right investment decisions." This is, by the way, part of the $2B investment which the article notes Microsoft will spend on development next year. The so called "far more than expected," according to analysts, which sent the stock plummeting two Friday's ago.

As I wrote last fall in a post about Gates and Steve Jobs, and their respective business efforts, I believe this entire approach by Gates and Microsoft will fail to reignite the firm's total return performance. The reason is the same as I articulated in the prior post, even considering that now the subject is a clone of Google's AdSense.

My friend S, the consultant to whom I referred in my recent Intel posts, and I discussed this point. She expressed disbelief that anything could really be different if Microsoft spent the same money on a separately-organized and funded effort that was physically and organizationally removed from the parent. I remain convinced it would.

How many of us have not worked in very large corporations, and watched how cultural forces mangle, compromise and choke the life out of new initiatives?

Microsoft is primarily a desktop software company. That is where it has made the bulk of its money, and produced the bulk of its deliverables. Trying to suddenly graft "online" onto it is a mistake.

As an example of this, my partner regaled me yesterday with his tale of attempting to install the new MS Internet Explorer browser version on his computer. It wasn't pretty. Firefox installed in a few minutes, flawlessly. He told me IE took 40 minutes, with multiple reboots every time the program failed to mesh with its own firm's registry software. Can it get much more pathetic than that? Microsoft controls both the OS and the browser, to the consternation of the regulatory authorities, and still can't get them to work together seamlessly.

This type of legacy penalty is part of the reason why I see Microsoft falling way short of its objectives of stopping Google's domination of the online advertising business. The other, of course, is simply the stifling culture of a behemoth now grown large and less nimble.

Complementing this story is what I saw in the brief clips of Bill Gates being interviewed by Donnie Deutsch on Friday. Suffice to say, Bill doesn't inspire much fear or confidence in Microsoft's new objective of taking on Google. When asked what he'd tell the Google execs, were they in the audience, Bill replied, smiling nervously, "we're going to keep them honest."

Wow, talk about killer goals. He's going to 'keep 'em honest.' I'll bet Serge is quaking in his boots after that warning!

Bill went on to babble about "having fun," how all the researchers in the Microsoft labs are "having fun" working on online and advertising services. That Bill and the whole firm are still "having fun." Nary a single word about profit, growth, or total returns.

Not being a Microsoft shareholder, this doesn't really bother me. But if I were, "having fun" would not be the main objective I'd be wanting to hear from Chairman Bill. I think his billions have finally dulled his instincts for profitable competition. Now, it looks like he's just using public funding to boost his ego and settle competitive business grudges.

Corporate Governance and Corporate Performance

With all the rage over corporate governance these days, I notice the omission of what I believe is the most important aspect of this function: oversight of the corporation's performance for shareholders. This historically has entailed some sort of "maximization of shareholder value," to use the phrase so many of us schooled at graduate schools of business were taught.

But what does that term really mean? When it's applied to a bond, the discounted cash flow formula is appropriate. It's not for equities. There are two reasons for this.

First, a very large number of equities experience growth in earnings which exceed the discount rate, causing the formula to be 'modified,' which, in essence, means it's the wrong formula for the job. Second, when applied to equities, the formula typically entails the use of an assumed "terminal value." This is done to make the math easier, as very distant cash flows begin to have apparently decreasing values, at a rather fast clip, due to the magic of compounding/discounting.

Over lunch with my partner the other day, our discussion of this topic clarified some nuanced points for me. Specifically, the concept or notion of running a company for some "maximized shareholder value" is wrong because of the terminal value implication. I've believed this for quite some time.What I believe is the proper valuation goal for a board, and a CEO, is "consistently superior (to the equity markets, i.e., S&P500) total returns over rolling 4-5 year periods." That is, ideally, a shareholder who buys a share of the firm at any time ought to have an equi-probably expectation of consistently superior total returns during a holding period of several years.

It is not sufficient, I believe, to simply choose, at some point in time, to 'maximize' the firm's value, at that time, for shareholders of record at that time. This would seem to contradict the notion of a continuing enterprise.Thus, if no single point in time is appropriate as that at which value is maximized, the firm should be managed to provide a consistently superior total return for as long a time as it can.

Saturday's Wall Street journal featured an interview with Charles Koch, CEO of the privately-held Koch Industries. Among other interesting passages was this, "...maintaining a business is, in reality, liquidating a business." He went on to refer to Schumpeterian dynamics in the internal management of a business. This is precisely my point. The business of managing a business is typically constant change- investment in, and destruction of, various parts of the business. This supposed ability to "maximize shareholder value" at some point in time is a fiction.

Rather, what should be targeted is as consistent as possible a total return performance which exceeds the market. This is because an investor can always buy the market return very inexpensively via an index fund. Thus, a CEO must offer an investor some reasonable expectation of outperformance of the index, on a consistent basis, in order to merit his company's stock being purchased, rather than the index. Stating that s/he has just "maximized shareholder value" for existing shareholders is hardlly going to attract new shareholders for the longer haul of a company's presumed existence.

Perhaps more companies would exhibit better total returns to investors if their boards focused on this challenge, rather than miscellaneous "governance" processes, or allowing a misguided focus on "maximized shareholder returns."

But what does that term really mean? When it's applied to a bond, the discounted cash flow formula is appropriate. It's not for equities. There are two reasons for this.

First, a very large number of equities experience growth in earnings which exceed the discount rate, causing the formula to be 'modified,' which, in essence, means it's the wrong formula for the job. Second, when applied to equities, the formula typically entails the use of an assumed "terminal value." This is done to make the math easier, as very distant cash flows begin to have apparently decreasing values, at a rather fast clip, due to the magic of compounding/discounting.

Over lunch with my partner the other day, our discussion of this topic clarified some nuanced points for me. Specifically, the concept or notion of running a company for some "maximized shareholder value" is wrong because of the terminal value implication. I've believed this for quite some time.What I believe is the proper valuation goal for a board, and a CEO, is "consistently superior (to the equity markets, i.e., S&P500) total returns over rolling 4-5 year periods." That is, ideally, a shareholder who buys a share of the firm at any time ought to have an equi-probably expectation of consistently superior total returns during a holding period of several years.

It is not sufficient, I believe, to simply choose, at some point in time, to 'maximize' the firm's value, at that time, for shareholders of record at that time. This would seem to contradict the notion of a continuing enterprise.Thus, if no single point in time is appropriate as that at which value is maximized, the firm should be managed to provide a consistently superior total return for as long a time as it can.

Saturday's Wall Street journal featured an interview with Charles Koch, CEO of the privately-held Koch Industries. Among other interesting passages was this, "...maintaining a business is, in reality, liquidating a business." He went on to refer to Schumpeterian dynamics in the internal management of a business. This is precisely my point. The business of managing a business is typically constant change- investment in, and destruction of, various parts of the business. This supposed ability to "maximize shareholder value" at some point in time is a fiction.

Rather, what should be targeted is as consistent as possible a total return performance which exceeds the market. This is because an investor can always buy the market return very inexpensively via an index fund. Thus, a CEO must offer an investor some reasonable expectation of outperformance of the index, on a consistent basis, in order to merit his company's stock being purchased, rather than the index. Stating that s/he has just "maximized shareholder value" for existing shareholders is hardlly going to attract new shareholders for the longer haul of a company's presumed existence.

Perhaps more companies would exhibit better total returns to investors if their boards focused on this challenge, rather than miscellaneous "governance" processes, or allowing a misguided focus on "maximized shareholder returns."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)