This morning, I heard CNBC "senior economic reporter" Steve Leisman's laughable explanation for his too-low estimate of the Labor Department's October jobs creation numbers.

He said he thought that weak productivity data over the past quarter would have led CEOs of large US companies to suspend hiring. I think this shows how out of touch he is with the way businesses run.

First, I doubt most CEOs can effect their company's employment levels with the speed of monthly data feeds. Typically, hiring for a given year is set late in the prior year's budget process, then possibly pre-empted by some crisis that leads to a hiring freeze in the current year. There's usually little in the way of alternatives in between.

Second, the labor dept report then added jobs to prior months, in their adjustment process, making the new-to-reporting additions of jobs soar over the past several months.

Essentially, the data made monkeys out of Leisman and all of his favorite on-air guest pundits. What did all these consulting sages do? They hemmed, they hawwed, and, in effect, complained that the data is of poor quality, and what we really need in this country is better economic data!

Translation: I got the estimate of new nonfarm payroll additions wrong this month, so the data is in error- again. I have my conclusions- now go get me the data to support them. If not this month, you just wait....any month now, job numbers will be down.

It reminds me of the constant bear market pundits of the early '90s. By calling for a bear market during pretty much the entire decade, they were finally able to be correct in 1999. But doesn't that equate to about a .100 batting average? I think something similar is going on here. Economic pundits get very angry when they play the 'estimate the number live on camera' game and get it wrong. So they explain why they'll soon be right, or the numbers are meaningless anyway.

I suppose it would be far too much to ask, or expect, that these pundits, starting with CNBC's Leisman, simply wait to interpret any of this data until it's been revised. Which one of my two favorite CNBC on-air personalities, Joe Kernan, explicitly suggested this morning. Suffice to say, Leisman's jaw nearly dropped at the suggestion, and he just looked dazed. Truth is, jumping on these numbers immediately upon initial release invites confusion and misinterpretation. Which is perhaps why I am so jaded about the misdirection and confusion sown by these economic wannabe-pundits throughout the year, affecting investor reactions and, thus, market prices of equities.

And that, dear readers, is entertainment, CNBC style......

Friday, November 03, 2006

CVS & Caremark To Merge: To What End?

Wednesday's announcement of a proposed merger between CVS and Caremark leaves me puzzled. I believe it is being portrayed as a purchase of the latter by the former, but technically being proposed to be accounted for as a merger of equals.

The crux of my bewilderment over the combination is that they are such different businesses. In effect, almost ideally contrasting ones. Didn't Caremark, Express Scripts, and Medco arise to undercut the costs of prescriptions being dispensed through local pharmacy chains like CVS? If so, how does one now reconcile a combination a bricks and mortar drug store chain with a remote medicinal order fulfillment giant?

Doesn't this remind you of the ill-fated TimeWarner/AOL merger? Didn't that merger resemble this one, in the combination of two radically different business models, in which one (AOL) had more or less evolved to supplant the other?

From a somewhat self-centered management perspective, I see the attraction. Messrs. Ryan and Crawford see themselves running a company that accounts for more than 25% of the country's prescriptions. Somewhere in there, I am sure they have reasoned, is enough scale to fend off Wal-Mart. Both CVS and Caremark has seen their stock prices fall roughly 15% in the past three months, and even more since early September, when Wal-Mart announced its entry into the low-price prescription drug business.

My guess is, CVS saw itself being drawn into the maw of price-competition by Wal-Mart, and panicked. Caremark probably expects Wal-Mart to eventually start its own PBM business, damaging the former's margins and market share position. From inside the barrel of existing sector players, this combination of CVS and Caremark probably looked like a reasonable way of building a larger, hedged liferaft to weather the coming competitive storms.

However, for each company's shareholders, I can't see what it offers. If you hold CVS for the retail exposure, this is not a deal you want to see occur. Similarly, if you hold Caremark because you think it will eventually strip the CVS's of the world of their prescriptions business, this deal makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. Further, how do you explain the combination of two businesses whose mechanics and operating models are so different? What are the odds that anyone will be capable of successfully running the combined entity to earn consistently superior total returns for its shareholders?

Better that Caremark would have reached some sort of deal with Wal-mart, if that could make any sense. Or that offer to ally with Wal-mart and place CVS mini-stores inside Wal-Mart. Of course, this would be extremely unlikely, precisely because CVS is about more than drugs. It's about broader retail convenience shopping.

I just cannot see a savvy investor in either CVS or Caremark saying, "Gee, this is great! This deal plugs that hole in the company's distribution model."

I can, however, see Ryan and Crawford feeling that they each have a more secure next five years of CEO or Chairman's compensation for heading a somewhat incongruous conglomerate of two businesses which are totally at odds in their missions and business models.

This type of schizophrenic combination does not, in my opinion, bode well for the longer term ability of either company to consistently earn superior total returns for shareholders, as part of the new combined firm.

The crux of my bewilderment over the combination is that they are such different businesses. In effect, almost ideally contrasting ones. Didn't Caremark, Express Scripts, and Medco arise to undercut the costs of prescriptions being dispensed through local pharmacy chains like CVS? If so, how does one now reconcile a combination a bricks and mortar drug store chain with a remote medicinal order fulfillment giant?

Doesn't this remind you of the ill-fated TimeWarner/AOL merger? Didn't that merger resemble this one, in the combination of two radically different business models, in which one (AOL) had more or less evolved to supplant the other?

From a somewhat self-centered management perspective, I see the attraction. Messrs. Ryan and Crawford see themselves running a company that accounts for more than 25% of the country's prescriptions. Somewhere in there, I am sure they have reasoned, is enough scale to fend off Wal-Mart. Both CVS and Caremark has seen their stock prices fall roughly 15% in the past three months, and even more since early September, when Wal-Mart announced its entry into the low-price prescription drug business.

My guess is, CVS saw itself being drawn into the maw of price-competition by Wal-Mart, and panicked. Caremark probably expects Wal-Mart to eventually start its own PBM business, damaging the former's margins and market share position. From inside the barrel of existing sector players, this combination of CVS and Caremark probably looked like a reasonable way of building a larger, hedged liferaft to weather the coming competitive storms.

However, for each company's shareholders, I can't see what it offers. If you hold CVS for the retail exposure, this is not a deal you want to see occur. Similarly, if you hold Caremark because you think it will eventually strip the CVS's of the world of their prescriptions business, this deal makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. Further, how do you explain the combination of two businesses whose mechanics and operating models are so different? What are the odds that anyone will be capable of successfully running the combined entity to earn consistently superior total returns for its shareholders?

Better that Caremark would have reached some sort of deal with Wal-mart, if that could make any sense. Or that offer to ally with Wal-mart and place CVS mini-stores inside Wal-Mart. Of course, this would be extremely unlikely, precisely because CVS is about more than drugs. It's about broader retail convenience shopping.

I just cannot see a savvy investor in either CVS or Caremark saying, "Gee, this is great! This deal plugs that hole in the company's distribution model."

I can, however, see Ryan and Crawford feeling that they each have a more secure next five years of CEO or Chairman's compensation for heading a somewhat incongruous conglomerate of two businesses which are totally at odds in their missions and business models.

This type of schizophrenic combination does not, in my opinion, bode well for the longer term ability of either company to consistently earn superior total returns for shareholders, as part of the new combined firm.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Kevin Roberts' New Clothes: Saatchi & Saatchi's "LoveMarks"

I guess the ad agencies are in need of another round of concept reinvention to invigorate client spending. Thus, Kevin Roberts, the CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi, appeared on CNBC this morning, touting his agency's latest technology, "LoveMarks."

As an aside, is it my imagination, or are ad agency heads who hope to be viewed as super-creative typically bald? I've nothing against bald men, but it does seem sort of iconic, does it not? Roberts put me in mind of Jerry Dela Famina when I saw him on CNBC this morning.

According to Roberts, this new concept is beyond product, beyond branding. It focuses on measuring and establishing emotional connections between products or services, and their customers. As described on their website, LoveMarks possess "mystery, sensuality, and intimacy."

Over the years, listening to many CEOs, I've learned to reserve conferring credibility on senior executives, until they either make sense, perform unequivocally well, or give themselves away as being delusional.

As I listened to Roberts describe McDonalds, I knew he was wrong, and pursuing the delusional path.

First, his throwaway comment that you won't find the "LoveMark" ideas at the B-schools like Wharton, Stanford, et al, is entirely wrong.

The highly-regarded marketing Professor from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, Jerry Wind, was teaching this concept in 1978. I know- I was in his classes, one of his PhD candidates, and one of his teaching assistants.

Sorry Kevin- your ego seems to have totally eclipsed any awareness you may have of the marketing field, absent your own genius.

Second, his characterization of what people want from products, brands, is, I think, at best, representative or characteristic of a tiny slice of consumers. It sounds like one of the (now defunct) Concorde set opining on what his seatmates want in high-end luxury products and services.

The broad masses of consumer goods buyers, however, live very different lives. Products don't always work, they aren't bought exclusively for the lifestyle image, as they are for sheer problem solution.

Listening to him extol McDonalds as an example of a LoveMark brought laughter from me. Roberts claimed that the brand is really about fun and family experiences, not fries, burgers or soft drinks.

Wrong again. First, my daughters won't even set foot in a McDonalds. They judge the fries as inferior to Burger King's. Same with the burgers- it's flame broiled for my brood.

When we travel, we tend to prefer Burger King, but mostly for their superior fast food salads.

I imagine that Roberts and his minions are having another go at the ad agency world's version of the "wheel of retailing." Every few years, one agency develops a 'new' concept, and most of the others soon follow on.

As I recall, the last major concept was integration. Saatchi merged its way to unsustainable size, only to find that clients didn't actually want to share ad agencies with their competitors. And they didn't really trust one global agency with all of their local work, either.

I'd guess LoveMarks is something similar. If Roberts can persuade a few Fortune 500 CEOs with his pitch, it's worth a few major accounts. And, from the sound of it, the package will probably include very involved customer surveys, creative sessions, etc. Should bring tons of billable hours.

Trouble is, as I learned from Jerry Wind those many years ago, not every segmentation scheme, nor product/service differentiator, is applicable to every product/market. Here's an example- do you think there's as much mystery and sensuality in buying dog food and your SO/wife's jewelry? Do you want to explain this to her? I thought not.

These dimensions either limit the concept to products and services which tend toward ego-involving purchases and usage, or they are rendered fairly meaningless as they are applied to items as insignificant as the toothpicks I buy.

Of course, being me, I have to ask.....do "LoveMark" products exhibit consistently superior total returns in the marketplace of investors? If not, or if this can't be measured, then I'm sceptical (hey, it's my blog title) that this concept contains much in the way of new, useful insights into consumer behaviors and corresponding business management.

As an aside, is it my imagination, or are ad agency heads who hope to be viewed as super-creative typically bald? I've nothing against bald men, but it does seem sort of iconic, does it not? Roberts put me in mind of Jerry Dela Famina when I saw him on CNBC this morning.

According to Roberts, this new concept is beyond product, beyond branding. It focuses on measuring and establishing emotional connections between products or services, and their customers. As described on their website, LoveMarks possess "mystery, sensuality, and intimacy."

Over the years, listening to many CEOs, I've learned to reserve conferring credibility on senior executives, until they either make sense, perform unequivocally well, or give themselves away as being delusional.

As I listened to Roberts describe McDonalds, I knew he was wrong, and pursuing the delusional path.

First, his throwaway comment that you won't find the "LoveMark" ideas at the B-schools like Wharton, Stanford, et al, is entirely wrong.

The highly-regarded marketing Professor from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, Jerry Wind, was teaching this concept in 1978. I know- I was in his classes, one of his PhD candidates, and one of his teaching assistants.

Sorry Kevin- your ego seems to have totally eclipsed any awareness you may have of the marketing field, absent your own genius.

Second, his characterization of what people want from products, brands, is, I think, at best, representative or characteristic of a tiny slice of consumers. It sounds like one of the (now defunct) Concorde set opining on what his seatmates want in high-end luxury products and services.

The broad masses of consumer goods buyers, however, live very different lives. Products don't always work, they aren't bought exclusively for the lifestyle image, as they are for sheer problem solution.

Listening to him extol McDonalds as an example of a LoveMark brought laughter from me. Roberts claimed that the brand is really about fun and family experiences, not fries, burgers or soft drinks.

Wrong again. First, my daughters won't even set foot in a McDonalds. They judge the fries as inferior to Burger King's. Same with the burgers- it's flame broiled for my brood.

When we travel, we tend to prefer Burger King, but mostly for their superior fast food salads.

I imagine that Roberts and his minions are having another go at the ad agency world's version of the "wheel of retailing." Every few years, one agency develops a 'new' concept, and most of the others soon follow on.

As I recall, the last major concept was integration. Saatchi merged its way to unsustainable size, only to find that clients didn't actually want to share ad agencies with their competitors. And they didn't really trust one global agency with all of their local work, either.

I'd guess LoveMarks is something similar. If Roberts can persuade a few Fortune 500 CEOs with his pitch, it's worth a few major accounts. And, from the sound of it, the package will probably include very involved customer surveys, creative sessions, etc. Should bring tons of billable hours.

Trouble is, as I learned from Jerry Wind those many years ago, not every segmentation scheme, nor product/service differentiator, is applicable to every product/market. Here's an example- do you think there's as much mystery and sensuality in buying dog food and your SO/wife's jewelry? Do you want to explain this to her? I thought not.

These dimensions either limit the concept to products and services which tend toward ego-involving purchases and usage, or they are rendered fairly meaningless as they are applied to items as insignificant as the toothpicks I buy.

Of course, being me, I have to ask.....do "LoveMark" products exhibit consistently superior total returns in the marketplace of investors? If not, or if this can't be measured, then I'm sceptical (hey, it's my blog title) that this concept contains much in the way of new, useful insights into consumer behaviors and corresponding business management.

Here We Go...... LX.TV Lifestyle Television Hits The Web

Tuesday's Wall Street Journal featured an article about a new internet site offering high-quality, new video content specifically produced for this site.

As I wrote here, and here, it was only a matter of time until some smart, funded directors and producers established their own website to offer new video content directly to viewers, without broadcast or cable networks.

Two MTV veterans have launched Lifestyle Television at LX.TV. Right now, it's primarily, as my consultant friend S, describes it, a series of commercials about luxury goods, without the bother of a plot or drama to interrupt them. As she said, it's as if Morgan Hertzan and Joseph Varet, the founders, learned from MTV and have eliminated the dramatic content, to focus on the more-lucrative advertising and placement revenues.

Seriously, LX.TV represents the onset of a business model which could well eventually drive high-quality drama off of even cable TV. For now, the content could be described as a high-quality video shot by following some twenty-something beautiful people in Manhattan around after hours. After seeing one segment about a $200 drink made with ingredients from one of the site's sponsors, S opined that, with topics like this, even she would consider joining Al Queda to fight the decadent West.

Nevertheless, I think the debut of LX.TV heralds the coming of direct-to-viewer dramatic video content over the internet. The founders are established creative and business executives from the cable world. They are starting by featuring personalities from cable networks, thus legitimizing the site, as well as lending more viewer interest in the programming.

When iTV arrives from Apple next summer, the technical pieces will be complete for viewing sites like LX.TV on your television. Add better dramatic content, a payment mechanism such as PayPal, and there's no reason why more established production companies won't begin developing new dramatic content for their own websites.

The future of direct-to-consumer video content has arrived.....

As I wrote here, and here, it was only a matter of time until some smart, funded directors and producers established their own website to offer new video content directly to viewers, without broadcast or cable networks.

Two MTV veterans have launched Lifestyle Television at LX.TV. Right now, it's primarily, as my consultant friend S, describes it, a series of commercials about luxury goods, without the bother of a plot or drama to interrupt them. As she said, it's as if Morgan Hertzan and Joseph Varet, the founders, learned from MTV and have eliminated the dramatic content, to focus on the more-lucrative advertising and placement revenues.

Seriously, LX.TV represents the onset of a business model which could well eventually drive high-quality drama off of even cable TV. For now, the content could be described as a high-quality video shot by following some twenty-something beautiful people in Manhattan around after hours. After seeing one segment about a $200 drink made with ingredients from one of the site's sponsors, S opined that, with topics like this, even she would consider joining Al Queda to fight the decadent West.

Nevertheless, I think the debut of LX.TV heralds the coming of direct-to-viewer dramatic video content over the internet. The founders are established creative and business executives from the cable world. They are starting by featuring personalities from cable networks, thus legitimizing the site, as well as lending more viewer interest in the programming.

When iTV arrives from Apple next summer, the technical pieces will be complete for viewing sites like LX.TV on your television. Add better dramatic content, a payment mechanism such as PayPal, and there's no reason why more established production companies won't begin developing new dramatic content for their own websites.

The future of direct-to-consumer video content has arrived.....

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

TimeWarner's Strategic Woes In Microcosm: Time, Inc.'s Troubles

There was an article in Monday's Wall Street Journal covering TimeWarner's troubles at its flagship magazine, Time, and the entire Time, Inc. portion of the business. From the article, we learn that "Queen Ann" Moore, Time, Inc's CEO, has totally botched the management of TW's magazine empire in the face of new media competition from- where else- the internet. Advertising revenues from Time's titles are plunging, as spending migrates to the internet, via Google, et al.

It looks like Dick Parsons is presiding over the erosion of a core business, and still doesn't know what is driving TW's stock price. There's a lot of hubbub right now over TW's recent stock price rise, as if it is "turning around." For more on this topic, see my recent post, here. Three months, however, do not a turnaround make. Not when one of the company's main businesses is hemorrhaging revenues, due to inept strategic management and planning.

As the Yahoo-sourced chart nearby shows (click on the chart to enlarge), over the past 3 months, TW has risen some 20%, while the S&P is up less than 10%. However, looking at 2 year (below) and 5 year (unable to get Blogger to paste it) charts, TW and the index are both up about 20% for the first period, but TW is down slightly less than 50% for the second period, while the S&P is up between 20% and 30%.

As the Yahoo-sourced chart nearby shows (click on the chart to enlarge), over the past 3 months, TW has risen some 20%, while the S&P is up less than 10%. However, looking at 2 year (below) and 5 year (unable to get Blogger to paste it) charts, TW and the index are both up about 20% for the first period, but TW is down slightly less than 50% for the second period, while the S&P is up between 20% and 30%.

The WSJ piece provides some insights into what has gone wrong with the magazine group under Moore's stewardship. Although the article quotes Moore as saying,

"Everyone is so worried that we're late coming to the party....this party is not over...The party just started. We've gotten to the real tipping point. The one thing I've learned this year is that there is a real business here."

Now, that is sad. Only this year has Moore realized what Google, Yahoo and other online sites have known for some time- that people now receive their important news online. Breaking news is online, and immediate followup coverage of breaking news can be in the form of a daily newspaper. But the weekly plain vanilla "news" magazine is in trouble, i.e., Time. That Sports Illustrated and CNNMoney are the major recipients of Time, Inc.'s online attentions only highlight that they do not cover typical, generic news topics.

Moore has had the top job at Time, Inc. for four years now, but, before that, was credited, in her 28 years with the company, with a knack for creating new titles, such as InStyle and Real Simple.

However, one only needs to step back and view the overall media landscape to see that Moore is probably as wrong a fit for her job as Parsons is for his. The company overall, and its magazine division particularly, suffer from being an old media giant, with its assets and brand values rooted in print distribution, while most of the people who value that information have already headed for the internet to find such content. That Moore thinks the game is just starting demonstrates how seriously she misunderstands the manner in which media consumption habits are developed, and brands are built. Meanwhile, her boss, Parsons, was characterized on CNBC this morning as being a "diplomat," selected to replace Gerald Levin at a time of tremendous organizational crisis at the firm, in the wake of the AOL merger disaster. Now, Parsons' skills as a lawyer and mediator seem badly deficient for the rather basic task of operational management of the current business portfolio, and strategic development of it for the future.

Again, taking that large step backward to view overall media, you can see that, with internet-based information distribution, the old boundaries between print and video, instant, daily, weekly, and monthly, are gone. Content distribution, consumer consumption, and, with them, advertising, have all been migrating to the web in increasing volumes. In this environment, what tangible value propositions do print magazines like Time and People now offer?

The Journal article mentions that, among the alternatives being discussed, is to make Time more like The Economist. I subscribe to the latter, and I frankly can't ever see the former mounting a serious challenge. Part of what makes The Economist what it is, is the international outlook from its British base. I doubt that Time will never be able to match that, let alone attract the talent to deepen its analytical capabilities.

Truth is, TW is holding media assets that are dwindling in value, as the plunging ad revenues indicate. Thus, the layoffs and cost-cutting at Time, Inc., parallel similar actions at the nation's struggling newspapers. As further evidence of both the magnitude of the problem, and the ineptitude and lack of confidence of the division's management, it has retained McKinsey to study its options for solutions.

All of which causes me to ignore the recent bounce in TW's stock price, and take, as usual, my longer-term view. I think this company is only gaining value for short-term reasons; either a divestiture of AOL, or radical one-time cost cuts which may fall to the bottom line. But on an ongoing basis, I believe the company's brands are, for the most part, damaged goods. The management team isn't up to fixing them, or even competently developing a strategy to maximize the value to shareholders of what's left. That's why they called in McKinsey.

In my opinion, TimeWarner will continue to deliver, over the long term, inferior total returns to its shareholders, while it is still around in its current incarnation.

It looks like Dick Parsons is presiding over the erosion of a core business, and still doesn't know what is driving TW's stock price. There's a lot of hubbub right now over TW's recent stock price rise, as if it is "turning around." For more on this topic, see my recent post, here. Three months, however, do not a turnaround make. Not when one of the company's main businesses is hemorrhaging revenues, due to inept strategic management and planning.

As the Yahoo-sourced chart nearby shows (click on the chart to enlarge), over the past 3 months, TW has risen some 20%, while the S&P is up less than 10%. However, looking at 2 year (below) and 5 year (unable to get Blogger to paste it) charts, TW and the index are both up about 20% for the first period, but TW is down slightly less than 50% for the second period, while the S&P is up between 20% and 30%.

As the Yahoo-sourced chart nearby shows (click on the chart to enlarge), over the past 3 months, TW has risen some 20%, while the S&P is up less than 10%. However, looking at 2 year (below) and 5 year (unable to get Blogger to paste it) charts, TW and the index are both up about 20% for the first period, but TW is down slightly less than 50% for the second period, while the S&P is up between 20% and 30%.

The WSJ piece provides some insights into what has gone wrong with the magazine group under Moore's stewardship. Although the article quotes Moore as saying,

"Everyone is so worried that we're late coming to the party....this party is not over...The party just started. We've gotten to the real tipping point. The one thing I've learned this year is that there is a real business here."

Now, that is sad. Only this year has Moore realized what Google, Yahoo and other online sites have known for some time- that people now receive their important news online. Breaking news is online, and immediate followup coverage of breaking news can be in the form of a daily newspaper. But the weekly plain vanilla "news" magazine is in trouble, i.e., Time. That Sports Illustrated and CNNMoney are the major recipients of Time, Inc.'s online attentions only highlight that they do not cover typical, generic news topics.

Moore has had the top job at Time, Inc. for four years now, but, before that, was credited, in her 28 years with the company, with a knack for creating new titles, such as InStyle and Real Simple.

However, one only needs to step back and view the overall media landscape to see that Moore is probably as wrong a fit for her job as Parsons is for his. The company overall, and its magazine division particularly, suffer from being an old media giant, with its assets and brand values rooted in print distribution, while most of the people who value that information have already headed for the internet to find such content. That Moore thinks the game is just starting demonstrates how seriously she misunderstands the manner in which media consumption habits are developed, and brands are built. Meanwhile, her boss, Parsons, was characterized on CNBC this morning as being a "diplomat," selected to replace Gerald Levin at a time of tremendous organizational crisis at the firm, in the wake of the AOL merger disaster. Now, Parsons' skills as a lawyer and mediator seem badly deficient for the rather basic task of operational management of the current business portfolio, and strategic development of it for the future.

Again, taking that large step backward to view overall media, you can see that, with internet-based information distribution, the old boundaries between print and video, instant, daily, weekly, and monthly, are gone. Content distribution, consumer consumption, and, with them, advertising, have all been migrating to the web in increasing volumes. In this environment, what tangible value propositions do print magazines like Time and People now offer?

The Journal article mentions that, among the alternatives being discussed, is to make Time more like The Economist. I subscribe to the latter, and I frankly can't ever see the former mounting a serious challenge. Part of what makes The Economist what it is, is the international outlook from its British base. I doubt that Time will never be able to match that, let alone attract the talent to deepen its analytical capabilities.

Truth is, TW is holding media assets that are dwindling in value, as the plunging ad revenues indicate. Thus, the layoffs and cost-cutting at Time, Inc., parallel similar actions at the nation's struggling newspapers. As further evidence of both the magnitude of the problem, and the ineptitude and lack of confidence of the division's management, it has retained McKinsey to study its options for solutions.

All of which causes me to ignore the recent bounce in TW's stock price, and take, as usual, my longer-term view. I think this company is only gaining value for short-term reasons; either a divestiture of AOL, or radical one-time cost cuts which may fall to the bottom line. But on an ongoing basis, I believe the company's brands are, for the most part, damaged goods. The management team isn't up to fixing them, or even competently developing a strategy to maximize the value to shareholders of what's left. That's why they called in McKinsey.

In my opinion, TimeWarner will continue to deliver, over the long term, inferior total returns to its shareholders, while it is still around in its current incarnation.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

When Growth Goes Bad: Wal-Mart & JetBlue

Monday's WSJ carried an article by Justin Lahart in his "Ahead of the Tape" column. It looks like Mr. Lahart needs some remedial financial theory work.

Yesterday's piece focused on how Wal-Mart's and JetBlue's stock prices rose when the companies announced plans to trim growth, via spending cuts.

Mr Lahart's bolded lead sentence reads,

"Advice for companies looking to jump-start their stock price: Stop spending."

Well, Mr. Lahart, at least you got it half-right. What he has observed is a simple example of the effects of unprofitable growth. When it slows, the company's total return may actually rise. Hard as this may be to believe, this concept has actually been understood by business people across America for over a quarter of a century.

Thus, when badly managed companies announce the abandonment of badly implemented or reasoned spending on ill-advised growth strategies, their stock prices may well rise.

This by no means implies that companies such as Apple, Google, or other profitably and productively growing companies should trim their growth spending. However, Amazon, which has had management problems for some time, also saw its stock price benefit from an announcement concerning its slowing of spending on growth initiatives.

Conditionality is everything in these situations.

On a related note, on the same day, CNBC's resident human version of a ticker tape, Bob Pisani, on the floor of the NYSE, attempted to project Wal-Mart's slowing sales growth to the entire sector and economy.

Memo to Bob:

FYI, Wal-Mart undertook a massive retail merchandising transformation last year, and it has failed. This is a major reason why its sales are disappointing. It does not necessarily have any bearing on other, better managed retailers.

Best regards,

-The Reasoned Sceptic.

It's sort of scary- and perhaps appropriately so, on this Halloween afternoon- that CNBC disseminates such ill-informed, half-baked reasoning live from the exchange's floor, and implies that it constitutes "news" on which investors may rely for their portfolio management.

So, to summarize, we have one reporter at the nation's premier business daily, and the on-air reporter for the nation's major business news television channel, both missing the nuances of cause and effect in Wal-Mart's recent actions and announcement of disappointing sales performance. And, though differently, each reporter then erroneously attempted to base further conclusions about the economy on factors particular to Wal-Mart, and, in the case of the WSJ's Lahart, a few other mismanaged, investment-spending paring firms.

God save us from our national business news media "news" reporters.

Yesterday's piece focused on how Wal-Mart's and JetBlue's stock prices rose when the companies announced plans to trim growth, via spending cuts.

Mr Lahart's bolded lead sentence reads,

"Advice for companies looking to jump-start their stock price: Stop spending."

Well, Mr. Lahart, at least you got it half-right. What he has observed is a simple example of the effects of unprofitable growth. When it slows, the company's total return may actually rise. Hard as this may be to believe, this concept has actually been understood by business people across America for over a quarter of a century.

Thus, when badly managed companies announce the abandonment of badly implemented or reasoned spending on ill-advised growth strategies, their stock prices may well rise.

This by no means implies that companies such as Apple, Google, or other profitably and productively growing companies should trim their growth spending. However, Amazon, which has had management problems for some time, also saw its stock price benefit from an announcement concerning its slowing of spending on growth initiatives.

Conditionality is everything in these situations.

On a related note, on the same day, CNBC's resident human version of a ticker tape, Bob Pisani, on the floor of the NYSE, attempted to project Wal-Mart's slowing sales growth to the entire sector and economy.

Memo to Bob:

FYI, Wal-Mart undertook a massive retail merchandising transformation last year, and it has failed. This is a major reason why its sales are disappointing. It does not necessarily have any bearing on other, better managed retailers.

Best regards,

-The Reasoned Sceptic.

It's sort of scary- and perhaps appropriately so, on this Halloween afternoon- that CNBC disseminates such ill-informed, half-baked reasoning live from the exchange's floor, and implies that it constitutes "news" on which investors may rely for their portfolio management.

So, to summarize, we have one reporter at the nation's premier business daily, and the on-air reporter for the nation's major business news television channel, both missing the nuances of cause and effect in Wal-Mart's recent actions and announcement of disappointing sales performance. And, though differently, each reporter then erroneously attempted to base further conclusions about the economy on factors particular to Wal-Mart, and, in the case of the WSJ's Lahart, a few other mismanaged, investment-spending paring firms.

God save us from our national business news media "news" reporters.

Rx for Citigroup From the Wall Street Journal

This past weekend's Wall Street Journal contained an article with a prescription for Citigroup's future health. For a change, it's one with which I agree. At last, someone else sees that financial utilities cannot consistently grow profitably for long.

The WSJ piece suggests that Citi CEO Chuck Prince dismantle Citigroup. It's a good idea, and not just for Citi. Who knows, maybe it will catch on. I wrote about the similarities of the three large US commercial banks here in April, and about Citi here, in July, and about banking as a commodity here, more recently. Unfortunately, Blogger is not cooperating with my attempt to paste the one-year stock price performance chart for BofA, Citi and Chase. However, it depicts three nearly lock-step institutions, in terms of price moves.

In general, my point has been that none of these financial super-utilities has the slightest chance to consistently outperform the S&P500 anymore. A look at the nearby Yahoo-sourced chart (please click on the chart to see a larger version of it) of the five year performance of Citi, Chase, BofA and the S&P500 illustrates how consistently mediocre the banks have been. Citi is currently the only one which has not, on a point-to-point basis, outperformed the index over five years, although the other banks are doing so only thanks to a recent price runup. Citi, though, has underperformed the index for more than a year, and tracked it, at best, prior to that.

In general, my point has been that none of these financial super-utilities has the slightest chance to consistently outperform the S&P500 anymore. A look at the nearby Yahoo-sourced chart (please click on the chart to see a larger version of it) of the five year performance of Citi, Chase, BofA and the S&P500 illustrates how consistently mediocre the banks have been. Citi is currently the only one which has not, on a point-to-point basis, outperformed the index over five years, although the other banks are doing so only thanks to a recent price runup. Citi, though, has underperformed the index for more than a year, and tracked it, at best, prior to that.

None of these financial utilities will consistently earn superior total returns for their shareholders over time. They are simply too large, way beyond the minimum economic size required to operate a financial services business. And their attempts at coordination cost more than the value of the conglomerations.

None of these financial utilities will consistently earn superior total returns for their shareholders over time. They are simply too large, way beyond the minimum economic size required to operate a financial services business. And their attempts at coordination cost more than the value of the conglomerations.

As this longer term chart of stock prices depicts, Chase is the only bank to underperform the S&P over the 21 year period, but Citi ceased to outperform the index as of roughly 2000. It's noteworthy that all two of the banks, Chase and Citi, have essentially flat-lined their stock price performance since that year. BofA has merely tracked the S&P for the last few years. None of these financial titans appear to be able to break out of a rut underperforming or merely tracking what an investor can get for total returns from the broader market.

Thus, it can't hurt for Citi to begin undoing the damage that Sandy Weill did to it since his ascension to the top job there so many years ago. If the bank were successfully integrating all of its business in some non-linear, more-than-additive manner, it would show up in the total returns. But it isn't. Like GE, we have a conglomerate that now exists more for senior staff and executive job preservation than for shareholder value creation.

At this point, it's hard to see how shareholders would be worse off by owning, and being offered the opportunity to hold or sell, separated interests in mortgage banking, retail banking, brokerage, institutional banking, and insurance. Each of these Citi units is sufficiently large to self-fund, and would likely prosper when forced to compete and prosper on their own, rather than spend significant resources simply being a compliant part of a financial super-utility.

The WSJ piece suggests that Citi CEO Chuck Prince dismantle Citigroup. It's a good idea, and not just for Citi. Who knows, maybe it will catch on. I wrote about the similarities of the three large US commercial banks here in April, and about Citi here, in July, and about banking as a commodity here, more recently. Unfortunately, Blogger is not cooperating with my attempt to paste the one-year stock price performance chart for BofA, Citi and Chase. However, it depicts three nearly lock-step institutions, in terms of price moves.

In general, my point has been that none of these financial super-utilities has the slightest chance to consistently outperform the S&P500 anymore. A look at the nearby Yahoo-sourced chart (please click on the chart to see a larger version of it) of the five year performance of Citi, Chase, BofA and the S&P500 illustrates how consistently mediocre the banks have been. Citi is currently the only one which has not, on a point-to-point basis, outperformed the index over five years, although the other banks are doing so only thanks to a recent price runup. Citi, though, has underperformed the index for more than a year, and tracked it, at best, prior to that.

In general, my point has been that none of these financial super-utilities has the slightest chance to consistently outperform the S&P500 anymore. A look at the nearby Yahoo-sourced chart (please click on the chart to see a larger version of it) of the five year performance of Citi, Chase, BofA and the S&P500 illustrates how consistently mediocre the banks have been. Citi is currently the only one which has not, on a point-to-point basis, outperformed the index over five years, although the other banks are doing so only thanks to a recent price runup. Citi, though, has underperformed the index for more than a year, and tracked it, at best, prior to that. None of these financial utilities will consistently earn superior total returns for their shareholders over time. They are simply too large, way beyond the minimum economic size required to operate a financial services business. And their attempts at coordination cost more than the value of the conglomerations.

None of these financial utilities will consistently earn superior total returns for their shareholders over time. They are simply too large, way beyond the minimum economic size required to operate a financial services business. And their attempts at coordination cost more than the value of the conglomerations.As this longer term chart of stock prices depicts, Chase is the only bank to underperform the S&P over the 21 year period, but Citi ceased to outperform the index as of roughly 2000. It's noteworthy that all two of the banks, Chase and Citi, have essentially flat-lined their stock price performance since that year. BofA has merely tracked the S&P for the last few years. None of these financial titans appear to be able to break out of a rut underperforming or merely tracking what an investor can get for total returns from the broader market.

Thus, it can't hurt for Citi to begin undoing the damage that Sandy Weill did to it since his ascension to the top job there so many years ago. If the bank were successfully integrating all of its business in some non-linear, more-than-additive manner, it would show up in the total returns. But it isn't. Like GE, we have a conglomerate that now exists more for senior staff and executive job preservation than for shareholder value creation.

At this point, it's hard to see how shareholders would be worse off by owning, and being offered the opportunity to hold or sell, separated interests in mortgage banking, retail banking, brokerage, institutional banking, and insurance. Each of these Citi units is sufficiently large to self-fund, and would likely prosper when forced to compete and prosper on their own, rather than spend significant resources simply being a compliant part of a financial super-utility.

Monday, October 30, 2006

Corporate Governance : Firing the CEO

Today's Wall Street Journal is a gold mine of interesting articles and topics on which to comment.

For this post, I'll focus on the paper's Marketplace article, "How To Fire a CEO." The gist of the pieces is that few CEOs can, it appears, actually be fired for cause. Outside of grossly inappropriate personal behavior, fraud, or embezzlement, simple poor performance of the duties for which s/he is compensated does not, evidently, merit discharge of the modern CEO.

There seems to be a significant inconsistency between the CEO's office and even his or her executive team. Let's take Wal-Mart, for example. It has, I am sure, an SVP or VP of Sales. Sales, however, have been lackluster. The company's recent marketing strategies aren't working very well, and sales are disappointing.

Would we not expect, at some point, that Lee Scott, Wal-Mart's CEO, might replace his head of sales? And would this not be because that executive failed to meet his or her management objectives, presumably involving sales goals?

Why can't the board, upon extending a contract to a CEO, include performance objectives? As I wrote here in a prior post, why does a board not hire a CEO on terms which substantially enrich the CEO, on a lagged basis, if s/he meets growth and total return objectives, but does not if they are not met?

Some will argue that really qualified CEOs won't take that kind of risk. Really? I'd expect at least a few would rise to the challenge of running a large company, plus making substantially more if they succeed, than if they fail. Further, what does the company have to lose? Compensating a CEO to not succeed will probably just get you another Jeff Immelt, the now-wealthy, and becoming wealthier, under-performing CEO of GE.

Ought not sauce for the goose be sauce for the gander, as well? If a CEO can, and does, replace under-performing executives on her or his team, why does not the board of directors do likewise? Include performance objectives in the CEO's contract, and enforce them.

Here's the dirtiest little secret about that, by the way. At today's average CEO compensation levels of $11.8MM, as reported here by The Corporate Library, even a failure as CEO at a large-cap firm is well on the way to retirement after only a year's failure in the job. Changing compensation to more variable, and less fixed, as I suggested in the earlier linked post, will at least make failures less expensive for a company.

However, for starters, how about boards simply setting performance objectives for their CEOs, and then acting on failure to perform?

For this post, I'll focus on the paper's Marketplace article, "How To Fire a CEO." The gist of the pieces is that few CEOs can, it appears, actually be fired for cause. Outside of grossly inappropriate personal behavior, fraud, or embezzlement, simple poor performance of the duties for which s/he is compensated does not, evidently, merit discharge of the modern CEO.

There seems to be a significant inconsistency between the CEO's office and even his or her executive team. Let's take Wal-Mart, for example. It has, I am sure, an SVP or VP of Sales. Sales, however, have been lackluster. The company's recent marketing strategies aren't working very well, and sales are disappointing.

Would we not expect, at some point, that Lee Scott, Wal-Mart's CEO, might replace his head of sales? And would this not be because that executive failed to meet his or her management objectives, presumably involving sales goals?

Why can't the board, upon extending a contract to a CEO, include performance objectives? As I wrote here in a prior post, why does a board not hire a CEO on terms which substantially enrich the CEO, on a lagged basis, if s/he meets growth and total return objectives, but does not if they are not met?

Some will argue that really qualified CEOs won't take that kind of risk. Really? I'd expect at least a few would rise to the challenge of running a large company, plus making substantially more if they succeed, than if they fail. Further, what does the company have to lose? Compensating a CEO to not succeed will probably just get you another Jeff Immelt, the now-wealthy, and becoming wealthier, under-performing CEO of GE.

Ought not sauce for the goose be sauce for the gander, as well? If a CEO can, and does, replace under-performing executives on her or his team, why does not the board of directors do likewise? Include performance objectives in the CEO's contract, and enforce them.

Here's the dirtiest little secret about that, by the way. At today's average CEO compensation levels of $11.8MM, as reported here by The Corporate Library, even a failure as CEO at a large-cap firm is well on the way to retirement after only a year's failure in the job. Changing compensation to more variable, and less fixed, as I suggested in the earlier linked post, will at least make failures less expensive for a company.

However, for starters, how about boards simply setting performance objectives for their CEOs, and then acting on failure to perform?

Ford & GM: What Constitutes A "Turnaround?"

We keep hearing that GM is successfully turning itself around. That Alan Mulally, Ford's new CEO, is planning a turnaround for that ailing auto maker.

What constitutes a "turnaround?" How is it measured? Does it have to take place within some timeframe to qualify as a turnaround, as distinct from, say, an evolution? Or basic business management?

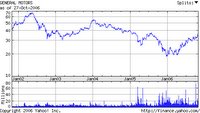

For example, look at the nearby Yahoo price chart (click on the chart to view an enlarged version) for Ford, GM, and the S&P500 for the past 12 months. To the casual eye, GM indeed appears to be "turning around," especially relative to the S&P and Ford.

However, as this second chart, depicting GM's stock price for the past five years, shows, it would not be the only time in the past 60 months that the company's stock price has rallied. However, each prior time, it subsequently fell. Given that this period contains the technology bubble burst, one might argue that that was the reason for the first selloff. In a sense, this makes my point. How many contextual factors must be considered, in order to judge a brief stock price move as a "turnaround?" Is Rick Wagoner correct in celebrating the twin victories of rebuffing Carlos Ghosn and reviving GM already? Or is GM's stock price, and total return, destined to head downward again within a few months, making investors have to time their buying and selling of GM quite finely in order to capture the temporary value gain in the stock?

However, as this second chart, depicting GM's stock price for the past five years, shows, it would not be the only time in the past 60 months that the company's stock price has rallied. However, each prior time, it subsequently fell. Given that this period contains the technology bubble burst, one might argue that that was the reason for the first selloff. In a sense, this makes my point. How many contextual factors must be considered, in order to judge a brief stock price move as a "turnaround?" Is Rick Wagoner correct in celebrating the twin victories of rebuffing Carlos Ghosn and reviving GM already? Or is GM's stock price, and total return, destined to head downward again within a few months, making investors have to time their buying and selling of GM quite finely in order to capture the temporary value gain in the stock?Is a turnaround measured in sales growth, or change in the rate of sales growth? Profit growth? Total return? All of these? Over what timeframes?

I'm curious, because when a firm like GM is claiming to already succeeding at its "turnaround," and then I hear and read analysis that casts doubt on their actual sales to end users, it gives me pause. It makes me think the entire concept has become a self-serving one.

And what about Alan Mulally's Ford Motor Company? It has a similar pattern to that of GM's stock price over the past five years, as the nearby chart illustrates. Twice in the past five years, its price has risen, only to slump, either quickly, or gradually over two and a half years.

And what about Alan Mulally's Ford Motor Company? It has a similar pattern to that of GM's stock price over the past five years, as the nearby chart illustrates. Twice in the past five years, its price has risen, only to slump, either quickly, or gradually over two and a half years.My own preference is to call a "turnaround" when a company's sales growth has placed it among the top large-cap or S&P companies on that measure, consistently, for several years. I feel the same about total returns. A few months, or even a year, of temporary sales growth and stock price rise does not, to me, sufficiently exceed normal S&P500 standard deviations from average performance to constitute anything more than random behavior.

For me, there's way too much going on in the auto sector to allow either Ford or GM to qualify for my portfolios any time soon. A genuine resurgence in sales, with accompanying profits that meet investors' expectations, over enough time to demonstrate lasting changes, not just one year's new models or one-off cost savings, will be required.

My portfolio strategy invests in companies which exhibit the hallmarks of consistently superior sales growth and total returns, not short-term gains, or long-term business uncertainty and inconsistencies in performance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)