This past week, Bill Griffith of CNBC began to speak of the return of "stagflation." In one of the network's seemingly endless "debates" between analysts whom they dig up from who knows where, Griffith asked both guests about "slowing" GDP growth and "rising" inflation possibly triggering the resurgence of the dreaded 1970's malady.

Talk about overreaction. The irony, of course, was that Griffith is old enough to actually recall stagflation, as am I, while his two guest economists were not. That said, Griffith sounded like some addled old codger.

Let me tell you, as far as "stagflation" goes, you ain't seen nothin' yet. Try interest rates at 18%. It's easy to read about it. But, you have to have actually lived in a functioning economy to understand it. Money market accounts yielding 12%. Lending still going on, but many loans simply refused, because bankers were too embarrassed to quote rates in the mid-20%'s, in order to cover risk.

And of course, inflation running in the teens.Yes, the 70s were truly a time of economic sickness. But it coincided with the years after the Fed was chaired by G. William Miller, surely one of the most inept men to have ever held the position.

Today, we have inflation running at a full 10 percentage points below what it was back in the late 1970s. Rates are a dozen percentage points lower as well. Using the word "stagflation" at this time, with this Fed, borders on irresponsible.

Additionally, we just had very strong global growth last year, and a torrid first quarter in the US. Basic economic activity is quite far from moribund. The private equity deals demonstrate how much confidence there is in current markets, that private investors are putting so much money directly into large businesses, in order to add even more value before spinning them back out.

Fortunately, both young economic pundits on the CNBC show that afternoon rapidly and forcefully dismissed Griffith of his mistaken notion. However, if there is any justice, he should have lost whatever on-air credibility he still had to that point.

With comments like "are we in danger of brink of stagflation" at this juncture in our economic history, Griffith makes a strong case for replacing him with someone of like business sense. Say, Regis Philbin or John Stewart?

Friday, June 09, 2006

Media's New Obsession: Misunderstanding the Fed

It seems that the majority of our country's business media feels that it, too, must vette Ben Bernanke's ascension to Chairman of the Federal Reserve System. Aside from Brian Wesbury's recent excellent op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal, most media pundits have been claiming that Bernanke is now focused on proving his credentials to them.

How drole. If you can't be Chairman of the Fed, tell everyone he has to prove himself to you. Thus, we have the untutored CNBC "senior economics correspondent" Steve Leisman babbling ceaselessly with his "guests" about Ben Bernanke's actions, thoughts, intentions, and performance. It's not that obtuse. I seriously doubt if Bernanke even cares what Leisman thinks or says.

Rather, as Wesbury wrote, Bernanke is busy simply repairing the damage of the on-again, off-again monetary policy which marked Alan Greenspan's last few years. Not to criticize Greenspan. He did a marvelous job under very difficult circumstances. However, the result of mopping up the aftermath of the burst technology investment bubble of 1999-2001 was some confusion as to which indicators to watch to manage monetary policy.

By historical standards, today's rates are very low. But direction and a sense of vigilance are important for the financial markets' long term health.

Despite the media's hand-wringing, the Fed continues to behave in the long term best interests of the US economy and financial markets. This past week's coordinated comments by Bernanke, Moskow, and the Atlanta Fed President, all addressing the current 2% rate of inflation as being 'at the high end of their comfort level,' were evidence of how effectively and professionally managed Federal Reserve System is. There is no mystery to anyone paying close attention to the FOMC members- they have repeatedly stated that their decisions on rate policies are data-driven.

The Fed is doing its job by managing inflation. The media continues to do its job of selling print/online eyeballs to advertisers by, when necessary, creating uncertainty where there is none.

How drole. If you can't be Chairman of the Fed, tell everyone he has to prove himself to you. Thus, we have the untutored CNBC "senior economics correspondent" Steve Leisman babbling ceaselessly with his "guests" about Ben Bernanke's actions, thoughts, intentions, and performance. It's not that obtuse. I seriously doubt if Bernanke even cares what Leisman thinks or says.

Rather, as Wesbury wrote, Bernanke is busy simply repairing the damage of the on-again, off-again monetary policy which marked Alan Greenspan's last few years. Not to criticize Greenspan. He did a marvelous job under very difficult circumstances. However, the result of mopping up the aftermath of the burst technology investment bubble of 1999-2001 was some confusion as to which indicators to watch to manage monetary policy.

By historical standards, today's rates are very low. But direction and a sense of vigilance are important for the financial markets' long term health.

Despite the media's hand-wringing, the Fed continues to behave in the long term best interests of the US economy and financial markets. This past week's coordinated comments by Bernanke, Moskow, and the Atlanta Fed President, all addressing the current 2% rate of inflation as being 'at the high end of their comfort level,' were evidence of how effectively and professionally managed Federal Reserve System is. There is no mystery to anyone paying close attention to the FOMC members- they have repeatedly stated that their decisions on rate policies are data-driven.

The Fed is doing its job by managing inflation. The media continues to do its job of selling print/online eyeballs to advertisers by, when necessary, creating uncertainty where there is none.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

Tesco's Exemplary Management

Tuesday's Wall Street Journal also carried a piece describing the superb marketing management of Tesco, the British grocery chain. It's wonderful to read of such sensible, informed, data-driven marketing and operations management in a large-scale firm.

That Tesco's skill has given Wal-Mart fits adds luster to the firm.

What struck me about Tesco's fundamental success ( the article does not mention, and I do not, presently, know its total returns for the past several years) is that it is really not much more than consistent, classic marketing management. Things I was taught almost 20 years ago at Penn's business school, where I studied marketing.

Tesco has combined its membership card with very good data analytics. Together, they allow Tesco's very capable managers to do that of which marketers always dream- know specific customer behaviors, and link pricing and product tactics to them.

The article describes both customer-segment management, as well as physical store management, using their member data. By comparing across stores, and customer segments, the Tesco management team has been able to add store features, products, etc, to both increase other store sales, as well as store sales in problem areas.

They really seem to have taken segmentation analyses, product strategy, and channel strategy about as far as I think I've seen it go, successfully.

What was illuminating was to read quotes from the managers of one of their lesser-performing competitors, Asda, who failed to appreciate the value of Tesco's member data. They really did not "get it." How powerful the combination of demographics, purchase data, and location are.

Again, as in my previous post regarding Howard Stringer at Sony, it's a pleasure to witness fine management in such a large-scale firm. These two pieces demonstrate what I mean when I write about the mediocre 70% of management. Here are two firms who are clearly way above that tranche. They either manage what they have in a consistently disciplined, successful manner, like Tesco. Or, like Stringer, they keep and refocus their assets and strengths, while coldly assessing their weaknesses and move to remedy those.

It's such a pleasure, amidst articles on GM, Intel, and Microsoft, to read about really self-aware, capably-managed firms like Tesco and Sony.

That Tesco's skill has given Wal-Mart fits adds luster to the firm.

What struck me about Tesco's fundamental success ( the article does not mention, and I do not, presently, know its total returns for the past several years) is that it is really not much more than consistent, classic marketing management. Things I was taught almost 20 years ago at Penn's business school, where I studied marketing.

Tesco has combined its membership card with very good data analytics. Together, they allow Tesco's very capable managers to do that of which marketers always dream- know specific customer behaviors, and link pricing and product tactics to them.

The article describes both customer-segment management, as well as physical store management, using their member data. By comparing across stores, and customer segments, the Tesco management team has been able to add store features, products, etc, to both increase other store sales, as well as store sales in problem areas.

They really seem to have taken segmentation analyses, product strategy, and channel strategy about as far as I think I've seen it go, successfully.

What was illuminating was to read quotes from the managers of one of their lesser-performing competitors, Asda, who failed to appreciate the value of Tesco's member data. They really did not "get it." How powerful the combination of demographics, purchase data, and location are.

Again, as in my previous post regarding Howard Stringer at Sony, it's a pleasure to witness fine management in such a large-scale firm. These two pieces demonstrate what I mean when I write about the mediocre 70% of management. Here are two firms who are clearly way above that tranche. They either manage what they have in a consistently disciplined, successful manner, like Tesco. Or, like Stringer, they keep and refocus their assets and strengths, while coldly assessing their weaknesses and move to remedy those.

It's such a pleasure, amidst articles on GM, Intel, and Microsoft, to read about really self-aware, capably-managed firms like Tesco and Sony.

Howard Stringer's New Sony Corp

Tuesday's Wall Street Journal featured a glowing piece on Howard Stringers, Sony's CEO. The article took the form of excerpts from Walt Mossberg's interview of Stringer at a recent conference on digitalization.

I have to say, from the piece, I like Stringer a lot. He seems to embody several great qualities in a leader. He seems both passionate, but deliberative as well. He has respect for his new company's strengths, but is wasting no time in remedying its weaknesses. He's not cowed by culture, nor language gaps. And he's not arrogant.

An acquaintance of mine from CBS had spoken glowingly of him there, when discussing his departure. She told me he also took a number of his best lieutenants with him to Sony. According to the article, he has also hired a key technology head from Apple, Tim Schaaff.

I like how Sir Howard appreciates Sony's vast product breadth, and finds strengths in it, as he also begins to pare back its excesses. He spoke eloquently about the new Sony Reader portable electronic book device. Stringer seems to share Steve Jobs' ability, in contrast to Bill Gates, to identify with his average customer, and passionately embrace a product he can "feel" is right.

From his remarks, I sense Stringer has the potential to fashion a turnaround at Sony by refocusing on successful exploitation of its classic strengths. By contrast, for instance, I think Gates and Microsoft are simply throwing money at new areas in which they have no particular advantage.

Sony isn't a member of the S&P500. I wish it were, because, based upon what I read this week, it could well become a good example of a firm on track to be consistently fundamentally strong and, then, consistently superior in its total returns to shareholders.

I have to say, from the piece, I like Stringer a lot. He seems to embody several great qualities in a leader. He seems both passionate, but deliberative as well. He has respect for his new company's strengths, but is wasting no time in remedying its weaknesses. He's not cowed by culture, nor language gaps. And he's not arrogant.

An acquaintance of mine from CBS had spoken glowingly of him there, when discussing his departure. She told me he also took a number of his best lieutenants with him to Sony. According to the article, he has also hired a key technology head from Apple, Tim Schaaff.

I like how Sir Howard appreciates Sony's vast product breadth, and finds strengths in it, as he also begins to pare back its excesses. He spoke eloquently about the new Sony Reader portable electronic book device. Stringer seems to share Steve Jobs' ability, in contrast to Bill Gates, to identify with his average customer, and passionately embrace a product he can "feel" is right.

From his remarks, I sense Stringer has the potential to fashion a turnaround at Sony by refocusing on successful exploitation of its classic strengths. By contrast, for instance, I think Gates and Microsoft are simply throwing money at new areas in which they have no particular advantage.

Sony isn't a member of the S&P500. I wish it were, because, based upon what I read this week, it could well become a good example of a firm on track to be consistently fundamentally strong and, then, consistently superior in its total returns to shareholders.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

More on Management Mediocrity- Part 2: Airlines

Yesterday's Wall Street Journal featured yet another piece on inept long-term management. This time, we were treated to an in-depth explanation of how major airlines have apparently chosen to manage ineptly for years.

According to the Journal's article,

"The improving financial results posted by seven of the nation's 10 big airlines in recent months reflect a fundamental shift in strategy....The big carriers, which for decades have doggedly pursued market share at any cost, now are focusing just as aggressively on the profitability of each route and flight."

Imagine that. Actually measuring profitability on a flight and route basis, then choosing to stop flying the unprofitable ones. What kind of management were shareholders of these '10 big airlines' paying for all those years- dart throwing? ouija boards?

It isn't really necessary to reiterate in detail what the well-written article states. Airline after airline has finally gotten serious about operating on profitable routes, and adjusting their size to fit. Load factors are now expected to reach 85% this summer.

Isn't it about time, for an industry that has frequently been described as having lost money, on a cumulative basis, since the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk at the dawn of the last century? According to the article, part of the profitability turnaround comes from a new generation of revenue management systems which allow for pricing decisions to take into account whether passengers are flying just one segment of a flight, or are a more lucrative passenger on a longer trip, of which the segment is but one part.

I'm reminded of the legendary Bob Crandall's comment that he wished he could have spun off American Airlines and kept the reservation system. Knowledge is power, and it looks like, in the airline industry, some rational managers, with better knowledge management tools, are finally gaining the upper hand.

Will this result in higher non-business fares and fuller airplanes? Doubtless. Of course, if that bothers you, why not wait til there's only one airline left on many routes, and pay their uncontested fare? Because the way things have been going, it's only a matter of time until something like that scenario was bound to occur.

I don't keep track, but so many airlines have been in, then out, then maybe back in, then out again, of Chapter 11, it's hard to recall the ones that have not filed for bankruptcy at some point.

That's no way to run a company, much less a sector. Business behavior like that signals too much capital committed to earn too few profits, and, thus, excess capacity. As if on cue, the article in the Journal notes that, these days, airlines are not chasing every expansion opportunity that occurs with a failed airline. Rather, they are focusing on development of added routes providing they are quickly and routinely profitable. What a concept!

Perhaps, in a backward-looking sort of way, airline executives have finally learned about consumer behavior in their business. Most non-business flyers appear to value price over brand, so that brand ubiquity added no value in that segment. Add in the ever-increasing pressure to avoid travel using email, instant messaging, and desktop- and laptop-based videoconferencing on inexpensive cameras, and you have a recipe for the disaster that occurred in the airline industry. Demand became hyper-price sensitive, and the internet contributed to the "discovery" of low prices, squeezing airline margins.

Apparently, empty feeder flights didn't deliver profitable customers and higher load factors when all routes are under pricing pressure.The eventual reaction, for airlines to survive, is to reduce capacity to the solidly profitable routes. It appears that in airline management, glamour is out, and sensibility is in.

Schumpeterian dynamics are alive and well in yet another part of our economy. And that, as usual, is a long term good thing for consumers and our economy.

According to the Journal's article,

"The improving financial results posted by seven of the nation's 10 big airlines in recent months reflect a fundamental shift in strategy....The big carriers, which for decades have doggedly pursued market share at any cost, now are focusing just as aggressively on the profitability of each route and flight."

Imagine that. Actually measuring profitability on a flight and route basis, then choosing to stop flying the unprofitable ones. What kind of management were shareholders of these '10 big airlines' paying for all those years- dart throwing? ouija boards?

It isn't really necessary to reiterate in detail what the well-written article states. Airline after airline has finally gotten serious about operating on profitable routes, and adjusting their size to fit. Load factors are now expected to reach 85% this summer.

Isn't it about time, for an industry that has frequently been described as having lost money, on a cumulative basis, since the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk at the dawn of the last century? According to the article, part of the profitability turnaround comes from a new generation of revenue management systems which allow for pricing decisions to take into account whether passengers are flying just one segment of a flight, or are a more lucrative passenger on a longer trip, of which the segment is but one part.

I'm reminded of the legendary Bob Crandall's comment that he wished he could have spun off American Airlines and kept the reservation system. Knowledge is power, and it looks like, in the airline industry, some rational managers, with better knowledge management tools, are finally gaining the upper hand.

Will this result in higher non-business fares and fuller airplanes? Doubtless. Of course, if that bothers you, why not wait til there's only one airline left on many routes, and pay their uncontested fare? Because the way things have been going, it's only a matter of time until something like that scenario was bound to occur.

I don't keep track, but so many airlines have been in, then out, then maybe back in, then out again, of Chapter 11, it's hard to recall the ones that have not filed for bankruptcy at some point.

That's no way to run a company, much less a sector. Business behavior like that signals too much capital committed to earn too few profits, and, thus, excess capacity. As if on cue, the article in the Journal notes that, these days, airlines are not chasing every expansion opportunity that occurs with a failed airline. Rather, they are focusing on development of added routes providing they are quickly and routinely profitable. What a concept!

Perhaps, in a backward-looking sort of way, airline executives have finally learned about consumer behavior in their business. Most non-business flyers appear to value price over brand, so that brand ubiquity added no value in that segment. Add in the ever-increasing pressure to avoid travel using email, instant messaging, and desktop- and laptop-based videoconferencing on inexpensive cameras, and you have a recipe for the disaster that occurred in the airline industry. Demand became hyper-price sensitive, and the internet contributed to the "discovery" of low prices, squeezing airline margins.

Apparently, empty feeder flights didn't deliver profitable customers and higher load factors when all routes are under pricing pressure.The eventual reaction, for airlines to survive, is to reduce capacity to the solidly profitable routes. It appears that in airline management, glamour is out, and sensibility is in.

Schumpeterian dynamics are alive and well in yet another part of our economy. And that, as usual, is a long term good thing for consumers and our economy.

Monday, June 05, 2006

More On Management Mediocrity: Time Warner's Example

Friday's Wall Street Journal featured an article on Time Warner that provided, a very revealing look into the troubled media conglomerate's strategic difficulties stretching back all the way to the 1990 merger of Time and Warner Brothers.

Rather than focus exclusively on Time Warner's many missteps throughout the years since 1990, I'd like to treat it as an excellent example of how companies which people believe are run by deep ranks of talented, intelligent senior executives are, in fact, mismanaged by the confused bungling of mostly mediocre, turf-protecting senior executives.

As the article discusses some of the changes in the media sector over the past decade, it quotes Sumner Redstone of Viacom saying,

"We had a lot of clout from size. Look at where it got us- nowhere. The world has changed a lot. Success depends to a large extent on your ability to adapt."

It seems a little late for Redstone to be now realizing these truths. Size hasn't counted for as much as it used to since, oh, when IBM lost its early lead in PCs in the late-1980s. And when has the ability to adapt ever not been useful? It would appear that, like Redstone and Viacom, the Ross-Levin-Parsons regime of Time Warner also failed to appreciate the necessities of successful adaptation to changing environments.

Apparently, Time Warner's history is full of various warring groups from Time, Warner, HBO, and AOL, depending upon the era, protecting their own, or trying to grab another internal group's turf, for internal financial advantage. This type of multi-divisional energy expenditure is a sure way for a large company to be come a smaller company, if not simply never become larger, over time. Time Warner seems to have done just fine on this measure of "success."

While current TW President Jeff Bewkes is pushing each unit to be unsubsidized, he still manages a conglomerate, each of whose acquisitions were partially sold on the benefits of integration and expense sharing. So, what he is essentially doing, by running TW as a group of independent units, is admitting that more than a decade of mergers and acquisitions were sold to investors for ultimately indefensible reasons.

I don't think I read in the piece that any of the ex-senior executives, such as Gerald Levin, Nick Nicholas, Steve Case, or Dick Parsons are giving any of their easily-won compensation back as recompense to misled investors.

And, yet, after years of lackluster shareholder return performance, Parsons still maintains, "if you have the sum of the parts under your control, you can sometimes get to the market faster."

Yes, and that is reflected where, in the firm's stock price performance, Dick?

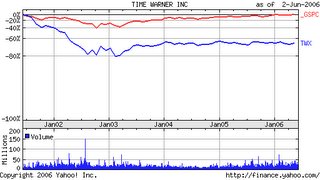

For background, I've pasted a Yahoo-sourced stock price chart for Time Warner, in comparsion with the S&P500, for the past five years. Prior to that, it is not clear whether the stock price used was AOL's, or Time Warner's, but it seemed to have been the former's, which would be moot for this post.

Viewing the chart, it's easy to see that TWX lost most of the 80% of value to the index by early 2003, and then slid a little bit more in the ensuing three years.

The WSJ piece further attributes to TW's 'executives' the belief that "...its breadth gives management a birds-eye view of the industry's shifting landscape and a better understanding of key issues."

Again, Time Warner seems to be able to do nothing for its shareholders with that 'birds-eye view and the 'better understanding of key issues.' My suspicion is that this is one of those cases in which a company would be better off dumping the unprofitably growing, or nongrowing divisions, and hire a tightly-controlled team of outside consultants to provide a cheaper 'birds-eye' view of the sector, from a truly objective perspective.

Media has surely been hit, and hit hard, by the incursion of digital technology over the last decade. It would be a pretty narrow-minded, dull management group indeed to believe that such dynamic value destruction and change in source of value creation, would lend itself to maintaining a large, slow-moving, bureaucratically-infighting-plagued conglomerate.

(Actually, as I write that, I'm reminded of Microsoft and Google, but that's for another post....)

As I wrote at the beginning of this piece, I don't wish to single out Time Warner, per se, for inept management, although they certainly have displayed it over the past five years. And, it appears from the WSJ article, if we could find the original Time Warner stock price history for 1990-2000, probably for that period as well.

Rather, I'd like to note how simply following the serial, failed expansions and merger integrations of more than a decade, alone, should have convinced a reasonable person that something was terribly amiss in the management of this company, or any company behaving in this fashion.

To continually destroy value via mergers, while simultaneously extolling the value of them, is ludicrous behavior. Why did anyone think the TW-AOL merger would ever work, with Time Warner's own checkered history of expansion?

Large firms often do have inept management. Track records of failure to consistently outperform the S&P500's total return do mean something. It's a shame that Time Warner has been able to reward senior management for fifteen years, while serially botching merger after merger, at their shareholder's expense.

My advice is, when you observe consistently mediocre, or worse, performance of a firm over several years time, take it seriously. Don't assume a turnaround is in the works any day soon. Don't assume the management responsible for the ongoing mediocre performance will wake up tomorrow, see reality, and change strategies on a dime. Rather, expect what you have heard from Dick Parsons of Time Warner for five years- continued justification for failed strategies and execution thereof. Then, sell the stock if you own it, and buy something with a better track record.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)