Saturday, June 03, 2006

Chicago Fed's Michael Moskow on CNBC

Nevertheless, Moskow's calm intellect and wisdom shone through. The Fed officer easily ignored Leisman's attempt to get him to divulge either Fed discussion details, or his own particular views on the coming meeting's decision for another rate hike.

What clearly emerged from Mr. Moskow's comments is a very confident, cautious, and experienced senior civil servant. He appears to be the type of experienced business person who makes you feel fortunate and more at ease, knowing he is on the job in his present position.

Ever mindful of the weight of his slightest remark, he simply reiterated that the recent data showing inflation running near 2% is at the high end of the Fed's announced comfort zone, and that the Fed is using developing data to guide its rate policies. Despite Leisman's efforts to pump him for "confidential" information, Moskow simply chuckled and ignored the questions.

The rest of the CNBC staffers on the show that morning had nothing better to ask of Moskow, either. Except for Becky Quick, whose question, I confess, I can't recall. It was inventive, but not really very informative.

It looks to me like the Fed really has its act together. Moskow's appearance sent a clear message that evolving economic data will continue to guide the group's interest rate moves, and that they will move to keep inflation from rising above the current level, which is at the upper range of their target zone.

It's helpful to keep this simple information in mind, because the business media will be trying relentlessly to concoct a news "story" about the impending Fed meeting's actions every day between now and that next meeting. Leisman was already busy, within an hour of the interview's end, with his "instant analysis" of the discussion. He apparently did not see the comical oxymoron in that phrase, in this instance.

Yes, there will be a lot more headlines to come. Fed-watching seems to be the topic that CNBC and other business media feel will sell the most airtime and print ads for the forseeable future.

Friday, June 02, 2006

Kinder Morgan's Private Buyout: Some Thoughts on the Larger Trend

Rather than discuss the pros and cons of this particular buyout, and the ethics of internal management, who know more about a company's prospects than anyone else, "offering to buy" a firm from other shareholders, I'd like to discuss the larger phenomenon of which this is the most recent example.

What may be the long term effects of a continuing series of private equity buyouts of publicly-held large-cap US firms? What does this mean for equity strategy managers, and investors in general?

First, consider why some firms are doing these buyouts. Sarbanes-Oxley has been mentioned as being both a source of the movement offshore of significant amounts of new business capital formation. A variant of that is to move business capital beyond the reach of the law by remaining in America, but going private.

If this continues, it's possible that one result is a near-term decline in the average return of indices of publicly-held companies, such as the S&P500. As the index replaces firms going private, one has to wonder if the replacements represent a pool of lesser-performing firms.

For an equity strategy like mine, the dynamic of outperforming the index doesn't really change. No matter what the average of the index, there will always be "above average" firms. Whether many of them are consistently superior is another question, but my expectation is that there will still be some which fit that criteria.

However, if the overall rates of returns available to public shareholders falls, it does nothing good for investors in general.

On the other hand, one has to wonder for how long private equity stays private. Isn't the ultimate goal to buy undervalued assets, improve their value, and spin them back out? If so, one would expect that these firms will begin to come out "the other end" of the buyout process, and release higher-valued firms into the publicly-held universe.

As higher-valued firms, one might expect their future returns to be less, since the value was built and taken out by the private equity groups. If this happens with sufficient frequency, perhaps buyout premiums will rise to clear the market of these deals in the first place.

If not, there is another phenomenon which may occur. I believe KKR was rumored, or is, structuring a sort of derivative cash-flow security based upon some of their gone-private entities. It seems that they are planning to slice up value of some of their private deals much like the way in which collateralized mortgage obligations slice the income streams from mortgage pools into differently performing tranches.

If this happens, we would see some elements of the publicly-held sector transformed into a sort of non-voting, non-operational claim on cash flows, and perhaps, value of businesses, without "shareholder" votes.

It's an interesting new development in long-term finance. It would also settle, in those cases, the issue of so-called "shareholder democracy" and "corporate governance." In a sense, it would be a modern twist on the "B shares" approach used by family companies gone public, such as Wrigley, Murdoch/Newscorp, and Dow Jones.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

Steve Ballmer Doesn't Get It

How stupid can you be? Really, for a guy this wealthy, having so much power at Microsoft, to say something so inane, makes you wonder why anyone would hold the firm's stock, doesn't it?

Having that much cash means the firm can't find risk-adjusted, profitable ways to spend it. They've run out of ideas that will add to shareholder value. Forget building truly better, more secure operating systems or application software. Or browsers. Instead, Bill and Steve are going windmill-tilting over near Google.

Am I the only one who sees it this way? Hasn't the issue of excess liquidity on balance sheets been resolved decades ago? And especially in this era of incredible liquidity from hedge funds and private equity firms? Excess cash on a firm's balance sheet is of no incremental value. Except to waste it, a la GM and Ford.

"Having" cash is no big deal. Putting it to value-creating work is. That's what Ballmer and Gates haven't done for the last five years.

Microsoft's salad days are over. Period. This type of senseless chest-beating on Ballmer's part, 'we have more cash than you do, and it is not a problem,' is further evidence of their failure to accept reality.

You want to talk about corporate governance? Where's the board of Microsoft on this one? Why haven't they stripped Chairman/Chief Software Architect Bill and CEO Steve of their jobs on behalf of the shareholders who have suffered below-market returns for the past five years? Why haven't they forced the use, or dividending of, the bulk of the $34.8B cash on the firm's balance sheet?

Now, that would take some fortitude. Does the lead outside director of Microsoft have it? The "official" Microsoft website does not reveal who that would be. But here are a few of the "winners" currently on the firm's board: Dina Dublon, former CFO of the mediocre JPMorganChase; Ray Gilmartin, recently deposed...err..retired CEO of Merck; Charles Noski, former Vice-Chairman of AT&T, a firm which self-destructed through incompetent senior executive leadership and mismanagement. I don't think this crew will be challenging Chairman Bill anytime soon about which way to steer the foundering S.S. Microsoft.

Enron Lessons From Jim Chanos

Chanos' first point is one I've believed for many years. It is that we need something other than rule-based, SEC-required accounting systems and audits.

Today's audits are a joke. They are the minimum effort required to pass SEC muster and keep everyone's insurance premiums for malpractice within reason. If you've ever read the actual statement by the auditing firm on the average 10K, then you know it's virtually worthless to investors.

I suggested, post-Enron and Tyco, that the SEC repeal the requirement for auditing. Then encourage auditing and insurance firms to team up and offer "platinum standard" audits which truly protect and inform shareholders. The implication would be, were an S&P500 firm to decline to purchase such and audit, that the firm's management was concerned it would not be given the seal of approval.

However, on the "carrot" side, imagine how much shareholder value would be created by paying for and passing a really tough audit. An audit that came with meaningful insurance covering the financial statements' accuracy and authenticity?

Sadly, in our current regulatory climate, we have over-regulation of the wrong kind, which only serves to drive new listings and capital formation activity overseas. If the Chinese get this right, while we continue to "enforce" current processes, be very afraid.

The second point I liked in Jim Chanos' piece is about sell-side analysts. He says that they "...don't "do" complex."

So true. Actually, they don't do very much at all that isn't sales-related, Elliot Spitzer notwithstanding. Chanos focuses on the weakness of the system, whereby senior analysts defer to the junior ones for technical replies to their understanding of companies which they cover.

I should be careful what I wish for here, because the existence of such narrowly-focused, junior analyst corps, really makes my own job easier. Sector-focused analysts help reduce the chances that others will observe what I have about the actual performance of consistently superior companies.

However, so long as people actually listen to these sell-side Street analysts, Enron-like situations will occur.

Finally, Chanos speaks to character. This is so crucial. Look around at some of the sitting CEOs of America's large-cap companies: Jeff Immelt, Jamie Diamond and Bob Nardelli, to name a few. What are we to think of executives who gladly take excessive compensation for mediocre performance? Do you think that someone who does that is magically going to try harder in order to continue to be lavishly paid? Not likely.

CEO compensation has to be dramatically rethought. But it starts with boards of directors who actually have a stake in the company's performance. It's a character issue all the way around.

In any case, I found Chanos' comments to be a delightful read, and very shrewd.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

New Tech Alliances- The Usual Suspects

It seems to me that it pretty much reinforces the various shifts in momentum and strength that have been evident for the last few years. To wit, Google is attacking Microsoft by pressing its advantage with a weakened Dell. Dell will now ship Google software pre-loaded on the computers it sells.

Yahoo will sell ads on eBay pages in the US, and correspondingly promote the latter's PayPal service on its own site. On this one, I'd say two troubled non-competitors are allying to maintain strength while not heading in the other's direction. Yahoo doesn't do auctions, and eBay doesn't do broad-spectrum information services, email, ads, nor groups.

The most predictable one, of course, is Microsoft. It is buying MotionBridge, a company involved in search software for mobile phones. Ballmer and Gates, you've got to love them. Financial indicators, market share data, no empirical evidence will stop these two from having fun at their shareholders' expense, will it?

Of all the linkups mentioned in the WSJ piece, the only one that doesn't make sense is Microsoft's. It doesn't remove a major competitor. It doesn't strengthen an existing product/market position. It's a "hail Mary" pass reminiscent of the firm's acquisition of WebTV. Does anyone else recall that one? I think it sank out of sight about three years ago. It was supposed to be Microsoft's easy pole vault into the living room, via a wireless keyboard and your TV screen.

Overall, the usual suspects have behaved as expected. The smarties at Google have exploited someone else's weakness and made further inroads onto desktops. Yahoo and eBay, perennial second-tier tech giants, keep out of each other's way, perhaps mutually fend off Google a bit, and don't give away anything valuable for nothing. Only Microsoft continues to be the Lone Ranger, straying ever further from its simple core strengths of desktop operating systems, applications, and browsers.

I doubt that any of these deals will markedly change current trajectories for the companies involved. They may avert slower growth, in the case of Google. Or even, in the case of Yahoo and eBay, protect each a bit more from competitive threats by Google. For Microsoft, it's just another expensive step on the way downhill- business as usual.

Lee Raymond's Exxon: Then and Now

Today's Exxon Mobil annual shareholder's meeting is providing a forum for the venting of anger regarding recently-retired CEO Lee Raymond's $400MM farewell compensation package.

My overall conclusion, based upon Exxon's failure to demonstrate consistently superior return performance over the period of Raymond's tenure as CEO, either as a high-growth, or low-growth company, is that he is being overpaid with this retirement package. As I've stated in several prior posts, I would simply sell the stock, if this really bothered me. In my case, though, I've already made an even stronger statement, by never buying Exxon stock in the first place.

Those who believe in "shareholder democracy," and that their withheld votes will change anything (as some state treasurer is reportedly doing today), are living in dreamland. Unless they can get some private equity firm to join them in controlling Exxon by way of a buyout, I don't think they are going to change the company all that much in the near future, from the outside. Perhaps their energy would be better spent finding other suitable companies in which to invest their capital, and depart the community of Exxon shareholders with their recent gains intact?

Or, they could heed my prior post regarding corporate governance reform, and attempt to change Exxon's board of directors, placing only those persons who hold millions of dollars of the stock bought with their own money in a position to oversee the CEO.

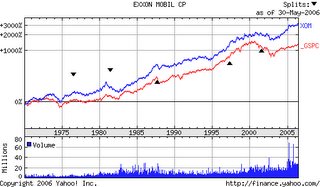

On the occasion of today's Exxon meeting, and the furor surrounding Raymond's payout, I did a little research on Exxon's performance, and the environment in which it has operated, going back some 25 years.

When I began working at AT&T in 1979, Exxon was still wrestling with its foray into telecommunications. The thinking back then was that oil was a business with limited future growth potential, so the firm should diversify into more promising businesses. I don't recall how many hundreds of millions of dollars Exxon poured into Exxon Enterprises, but suffice to say, the entire effort was shuttered within a decade. Even the alternative energy unit.

To say then, that Exxon has simply benefited from higher oil prices over the past 25 years is to misunderstand the number of business options available to the firm since the early 1980s, none of which they pursued, after the disastrous "diversification" program of the 1970s.

Rather, under Clifton Garvin, and then, Larry Rawl, the firm pared expenses, refocused on petroleum, and managed to survive in a world of $15/bbl oil. In fact, in articles I read this morning from that era, the firm was touted as very well managed simply for maintaining its income stream in the face of a very dismal market outlook for the forseeable future.

Following Rawl's departure, Lee Raymond took the helm, and merged with Mobil. Since then, the company has operated according to Raymond's signature style of tight expense management and cautious investment in refining and exploration.

However, looking at the Yahoo-sourced chart of Exxon's share price since 1970 shown above, you can see that most of the gains in the company's stock, versus the S&P500, are in brief bursts. Of course, there's a dividend payout that would increase the implied total return for Exxon. But assuming that's been relatively steady, the chart looks more like two ships tacking with each other in a race, than it does like some consistently outperforming company pulling ahead of the S&P over many years. The gap between the "ships" slowly narrows and widens over the years, but neither ever pulls decisively away from the other for very long.

I'm not disputing that Exxon has outperformed the index over a 35 year period. It has even clearly risen by much more than the index since 2000. However, it's not so much a consistent recent total return superiority as it is a few years of high returns.

From this perspective, nobody who has been CEO of Exxon since 1970 deserves a $400MM payout for a consistently superior job well done.

And, more to the point, would Lee Raymond have left early, or declined the CEO position, if he knew he would only receive, say, $50MM upon retirement?

Doubtful. It's not about the money for people who hold these positions. They'd do the job for far less, just to have that kind of power over an asset base of that size.

To me, the real culprits here, once again, are the board members, not the CEO. Exxon's board has unwisely squandered its shareholders' money when it almost certainly could have bought similar total return performance since 1993 for far less, even from Lee Raymond.

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Fannie Mae's Financial Fraud

Here we have Fannie Mae's erstwhile CEO, Franklin Raines, apparently guilty of brazen financial records manipulation to trigger massive senior executive bonus payments over several years, and Congress is livid over Lee Raymond's retirement package from ExxonMobil.

I find it troubling that we have the Federal government causing its own massive failure of "corporate governance," as well as "CEO compensation" reasonability, yet managing to turn a blind eye to the whole matter.

My friend B emailed me the 6-page abstract of the regulators' report concerning Raines & Co.'s financial chicanery. It was sickening to read. Fannie has extensive regulatory oversight, and with its access to our Federal government's implicit credit guarantees, should be much more tightly supervised. Instead, we have senior executive behavior that compares handsomely with Lay, Skilling and Fastow at Enron.

It's really a shame that the average US equity investor does not realize what went on at Fannie. Nor how complicit Congress is in not shining a bright light on the mess, and appropriately punishing those involved. Once again, we are treated to the sight of Federal government entities taking it easier on themselves and their colleagues than on the taxpaying public, whether individually or as corporations.

Raines was appointed by Clinton, a Democratic president. So it's not something the media and the House and/or Senate Democratic minority leadership can accuse Bush of arranging. Rather, it seems to continue to point up the basic weakness of allowing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac access to the Treasury on such favorable terms. Then turning around and using that massive financial power to influence Congress, district by district, to continue to support the housing institutions, or explain the presumed dearth of home mortgage funding availability to their constituents.

The whole mess should be ripped out by the roots, while allowing the substantial private mortgage lending sector to step up to replace Fannie Mae with competitive products at competitive prices, breaking the link between individual housing finance and Congressional largesse.

Monday, May 29, 2006

Jack Welch's Spawn: Nardelli's and Immelt's Pay & Performances

Last week saw a shareholder furor over the combination of Bob Nardelli's recent compensation as CEO of Home Depot with the stock's performance since he assumed the helm.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Nardelli "has received more than $100MM in salary, bonuses and stock awards, plus millions of dollars more in stock options, while the share price of Home Depot has declined by 12% during the same period." On Thursday of last week, every company director, except Nardelli, skipped the Home Depot annual shareholder's meeting. And Nardelli declined to answer questions regarding his compensation, ending the meeting after only 30 minutes.

What struck me, though, is how similar Nardelli is to the other famous spawn of Jack Welch's GE tenure- current GE CEO Jeff Immelt.

I've pasted a Yahoo chart of the two companies' stock price performances over the last five years, compared with the S&P500. For more details about Immelt's compensation, see my post here, entitled "Rewarding Losers- GE," written this past March.

Look at how similar the Home Depot and GE stock price paths are. It's almost like they are in the same industry. But they're not. Their two shared attributes are that each is headed by a former candidate for CEO of GE, and each company has paid it's former GE senior exec (in Immelt's case, now GE CEO and Chairman) handsomely to underperform the S&P500.