Friday's Wall Street Journal featured an article on Time Warner that provided, a very revealing look into the troubled media conglomerate's strategic difficulties stretching back all the way to the 1990 merger of Time and Warner Brothers.

Rather than focus exclusively on Time Warner's many missteps throughout the years since 1990, I'd like to treat it as an excellent example of how companies which people believe are run by deep ranks of talented, intelligent senior executives are, in fact, mismanaged by the confused bungling of mostly mediocre, turf-protecting senior executives.

As the article discusses some of the changes in the media sector over the past decade, it quotes Sumner Redstone of Viacom saying,

"We had a lot of clout from size. Look at where it got us- nowhere. The world has changed a lot. Success depends to a large extent on your ability to adapt."

It seems a little late for Redstone to be now realizing these truths. Size hasn't counted for as much as it used to since, oh, when IBM lost its early lead in PCs in the late-1980s. And when has the ability to adapt ever not been useful? It would appear that, like Redstone and Viacom, the Ross-Levin-Parsons regime of Time Warner also failed to appreciate the necessities of successful adaptation to changing environments.

Apparently, Time Warner's history is full of various warring groups from Time, Warner, HBO, and AOL, depending upon the era, protecting their own, or trying to grab another internal group's turf, for internal financial advantage. This type of multi-divisional energy expenditure is a sure way for a large company to be come a smaller company, if not simply never become larger, over time. Time Warner seems to have done just fine on this measure of "success."

While current TW President Jeff Bewkes is pushing each unit to be unsubsidized, he still manages a conglomerate, each of whose acquisitions were partially sold on the benefits of integration and expense sharing. So, what he is essentially doing, by running TW as a group of independent units, is admitting that more than a decade of mergers and acquisitions were sold to investors for ultimately indefensible reasons.

I don't think I read in the piece that any of the ex-senior executives, such as Gerald Levin, Nick Nicholas, Steve Case, or Dick Parsons are giving any of their easily-won compensation back as recompense to misled investors.

And, yet, after years of lackluster shareholder return performance, Parsons still maintains, "if you have the sum of the parts under your control, you can sometimes get to the market faster."

Yes, and that is reflected where, in the firm's stock price performance, Dick?

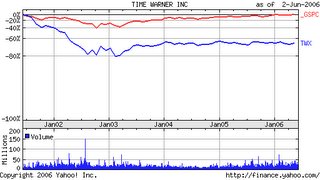

For background, I've pasted a Yahoo-sourced stock price chart for Time Warner, in comparsion with the S&P500, for the past five years. Prior to that, it is not clear whether the stock price used was AOL's, or Time Warner's, but it seemed to have been the former's, which would be moot for this post.

Viewing the chart, it's easy to see that TWX lost most of the 80% of value to the index by early 2003, and then slid a little bit more in the ensuing three years.

The WSJ piece further attributes to TW's 'executives' the belief that "...its breadth gives management a birds-eye view of the industry's shifting landscape and a better understanding of key issues."

Again, Time Warner seems to be able to do nothing for its shareholders with that 'birds-eye view and the 'better understanding of key issues.' My suspicion is that this is one of those cases in which a company would be better off dumping the unprofitably growing, or nongrowing divisions, and hire a tightly-controlled team of outside consultants to provide a cheaper 'birds-eye' view of the sector, from a truly objective perspective.

Media has surely been hit, and hit hard, by the incursion of digital technology over the last decade. It would be a pretty narrow-minded, dull management group indeed to believe that such dynamic value destruction and change in source of value creation, would lend itself to maintaining a large, slow-moving, bureaucratically-infighting-plagued conglomerate.

(Actually, as I write that, I'm reminded of Microsoft and Google, but that's for another post....)

As I wrote at the beginning of this piece, I don't wish to single out Time Warner, per se, for inept management, although they certainly have displayed it over the past five years. And, it appears from the WSJ article, if we could find the original Time Warner stock price history for 1990-2000, probably for that period as well.

Rather, I'd like to note how simply following the serial, failed expansions and merger integrations of more than a decade, alone, should have convinced a reasonable person that something was terribly amiss in the management of this company, or any company behaving in this fashion.

To continually destroy value via mergers, while simultaneously extolling the value of them, is ludicrous behavior. Why did anyone think the TW-AOL merger would ever work, with Time Warner's own checkered history of expansion?

Large firms often do have inept management. Track records of failure to consistently outperform the S&P500's total return do mean something. It's a shame that Time Warner has been able to reward senior management for fifteen years, while serially botching merger after merger, at their shareholder's expense.

My advice is, when you observe consistently mediocre, or worse, performance of a firm over several years time, take it seriously. Don't assume a turnaround is in the works any day soon. Don't assume the management responsible for the ongoing mediocre performance will wake up tomorrow, see reality, and change strategies on a dime. Rather, expect what you have heard from Dick Parsons of Time Warner for five years- continued justification for failed strategies and execution thereof. Then, sell the stock if you own it, and buy something with a better track record.

2 comments:

That we still seem able to fall for the old merger chestnuts is darkly humorous. The merger gets "sold" based on economies of scale, integration, synergy, better ability to explot new markets cross-functionally, etc. Then, when it turns out to be the typical horrible mess, an abrupt about-face and management starts talking about "unsubsidized units" and preaching that the behemoth will now be a collection of nimble, lean and mean entreprenuerial-type businesses.

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me 112 times . . .

From what I've seen, and this is a non-scientific observer's view, admittedly, there is a pont of diminishing returns with bigness. It's just too hard to manage, perhaps? Or, possibly -- there just aren't enough good managers for the divisions and sub-divisions? And certainly there seems to be real dearth of excellent talent right under the CEO level, which I think would be key, since above a certain size one person's influence, no matter how brilliant that person is, becomes one of tone, of orientation as opposed to actual "presence."

In most big mergers, the usual suspects get enriched. Rarely are those usual suspects shareholders, going forward.

Yes, I agree with your assessment of the role of extreme size in failed or disappointing mergers. The same seems to be true in even largely organically-managed companies.

The role of the broad mediocre middle of business executives is, I believe, vastly underestimated.

Post a Comment