I read the Wall Street Journal's recent piece entitled, "Changing Gears.... Inside Mulally's 'War Room': A Radical Overhaul of Ford."

I am so glad that I have not been a Ford stockholder. It's a good news/bad news sort of thing. The good news is that Mulally is smart, experienced, determined and energetic. I think it's great for Ford that Mulally is so talented. He does seem like a very competent, capable guy.

The bad news is that his boss, Bill Ford, let things get this bad. Tolerated crony pals mismanaging the firm, and that the board let it happen on their watch.

Now they all want Alan Mulally to work magic and fix the mess.

For example, the article mentions that Mark Schulz,

"Ford's 54-year-old head of international operations...would be changing jobs to a different role, with direct business responsibility...Mr. Schulz, a longtime fly-fishing and ice-hockey buddy of Mr. Ford, retired instead....(and) couldn't be reached for comment."

Sounds too precious, doesn't it? You can almost see Schulz mugging it up with Bill Ford over eggnog at the proper Gros Pointe country club holiday parties, wearing pleated slacks festooned with little ice-hockey sticks poking through Christmas wreathes, or fly-fishing rods catching Christmas stockings. This sort of thing drives employee morale into the toilet, I kid you not. Nothing infuriates capable lieutenants more than seeing the Boss socializing off-premises with also-ran managers who clearly curry favor and retain their positions thanks to friendships with the CEO, rather than their own performance or talent.

Meanwhile, Bill Ford let this continue as part of his "management" and "leadership" of his family firm.

In another part of the piece, Mulally is quoted as saying that, when he asked Bill Ford

"why he hadn't integrated the company....every time Ford had considered forcing integration, a new hit product- such as the Explorer, Taurus or F-series truck- would come along and propel profitability without tough changes, explained the fourth-generation Ford leader."

So to cronyism we can add lack of focus and discipline. The board and Bill Ford are hoping to God that Alan Mulally can do the dirty, harsh, odious work of firing loyal, trusting employees, redesigning bloated, dysfunctional corporate processes, and identifying new, hit products. Because for five years, as CEO, and six as a board member, Bill Ford failed to do all of these.

In fact, the Journal article related this exchange between Chairman Bill (Ford, not Gates) and board member John Thornton, former President of Goldman Sachs,

Ford: "Alan's the perfect guy for our situation."

Thornton: "I couldn't agree more. Thank God for that, we don't have a second chance. This is it."

What is it with Detroit auto company CEOs? Must they wait until they teeter on the edge of bankruptcy before shifting gears (pun intended)?

Is there time for Mulally to save Ford? Who knows? Is he doing some right things? Unquestionably. For instance, he drives each model of the firm's product line, the better to give it a personal, objective going-over. His comment about the lack of a standard "feel" for Ford cars is absolutely true. My father was a "Ford man" when I was growing up. In models of similar years, the controls were typically located in the same place. You knew you were in a Ford, not a GM car, just by the layout of the dashboard and knobs.

The WSJ piece lavishes much print on Mulally's rather unremarkable, if very effective, use of colors and graphic displays to track product-management issues in his 'war room.' That this technique, and his insistence on the divulging by managers of complete and true performance data, is more than shocking. It's disgraceful. Consider what it says about the lack of respect these managers have had for Mulally's predecessor.

Oh, wait....that's the sitting chairman......Bill Ford!

Will Mulally's sensible initiatives matter? Truthfully, I doubt they have the time. Still, oddly, I can't but help root for the guy. Maybe in 3-4 years, Ford will make my equity portfolio selection list. Although, my hunch is, not as an independent company. Perhaps as part of an alliance with Nissan. If it merges with GM, I would lower the probabilities of its performing sufficiently well to make my selection list.

Either way, 2007 will be exciting for lots of reasons, and Mulally's activities at Ford are just one.

Happy New Year!

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Friday, December 29, 2006

David Malpass on The US Trade Deficit

Bear Stearn's chief economist, David Malpass, wrote a wonderful piece in the Wall Street Journal last week. His topic was how the US deficit is misunderstood and misinterpreted by many observers. In this, he is but one of several to have authored op-ed pieces in the Journal to this effect over the last decade or so.

I won't go into detail about the many data items Malpass cites as he conditions his observations in the article. However, this passage is perhaps the piece's best distillation of his message,

"The common perception is that Americans drive the trade deficit in an unhealthy way by spending more than we produce. To make up the difference, foreigners ship us things on credit. This sounds bad, but should be evaluated in terms of our demographics, low unemployment rate, attractiveness to foreign investment and rising household savings (my bold)."

A little further, he continues,

"Growing corporations are expected to be cash hungry. This leverage is treated as a positive for companies, but a negative for countries, a key inconsistency in popular economics. Rather than paying back the debt back, the growing economy rolls the debt over and adds more, just as the U.S. has been doing throughout most of its prosperous economic history. Part of each additional bond offering puts the company and the U.S. in the position of investing more than we save, drawing in foreign investment and contributing to the trade deficit."

Together, these passages make Malpass' critical point, i.e., sovereign debt, and/or trade deficits, matter in the context of the country's economic trajectory. In our case, we have the largest, vibrant, resilient and attractive economy in the world. Despite what economic and political gloomsters would have you believe, we borrow at favorable rates because others wish to participate in our economic success. They hold dollars, or dollar-denominated debt, and invest in our country directly. We use that capital to grow. Malpass makes the point further in his article that American household net worth is growing faster than net foreign debt of the U.S.,

"meaning foreigners are investing in the U.S. too slowly and conservatively to keep up with our growth."

It's a nice problem that we have, actually. Our economy is the envy of the world, which is one reason why even The Economist has sounded like a broken record on this topic for as long as I can recall. Context matters. Context means everything in macroeconomic analysis. By the way, in one of the earlier Journal pieces on this topic, another author cited the late 1800s in the U.S. as a parallel economic period. We had significant growth and a large trade deficit, consistent with heavy imports to fuel our rapidly-industrializing young nation. While Abe Lincoln was right about a lot of things, he was wrong to worry about trade deficits.

It goes without saying that this type of nuanced analysis will go over the heads of most U.S. Senators and Congressmen, and probably most Presidential candidates as well.

It reminds me of something my father used to frequently say. When listening to yet another media criticism of low voter turnouts in some fall election, he would remark thusly,

'Son, you only get to vote once every four years for the President. But you vote each day with your dollars, and those have a much larger and frequent impact than your political vote.'

What I think this means, pursuant to this post, is that, despite most politicians, and even most economists, not understanding the real dynamics of our trade deficit, so long as our nation's citizens just continue to drive our economy as usual, the trade deficit will not be any more of a problem in the future than it has in the past.

I won't go into detail about the many data items Malpass cites as he conditions his observations in the article. However, this passage is perhaps the piece's best distillation of his message,

"The common perception is that Americans drive the trade deficit in an unhealthy way by spending more than we produce. To make up the difference, foreigners ship us things on credit. This sounds bad, but should be evaluated in terms of our demographics, low unemployment rate, attractiveness to foreign investment and rising household savings (my bold)."

A little further, he continues,

"Growing corporations are expected to be cash hungry. This leverage is treated as a positive for companies, but a negative for countries, a key inconsistency in popular economics. Rather than paying back the debt back, the growing economy rolls the debt over and adds more, just as the U.S. has been doing throughout most of its prosperous economic history. Part of each additional bond offering puts the company and the U.S. in the position of investing more than we save, drawing in foreign investment and contributing to the trade deficit."

Together, these passages make Malpass' critical point, i.e., sovereign debt, and/or trade deficits, matter in the context of the country's economic trajectory. In our case, we have the largest, vibrant, resilient and attractive economy in the world. Despite what economic and political gloomsters would have you believe, we borrow at favorable rates because others wish to participate in our economic success. They hold dollars, or dollar-denominated debt, and invest in our country directly. We use that capital to grow. Malpass makes the point further in his article that American household net worth is growing faster than net foreign debt of the U.S.,

"meaning foreigners are investing in the U.S. too slowly and conservatively to keep up with our growth."

It's a nice problem that we have, actually. Our economy is the envy of the world, which is one reason why even The Economist has sounded like a broken record on this topic for as long as I can recall. Context matters. Context means everything in macroeconomic analysis. By the way, in one of the earlier Journal pieces on this topic, another author cited the late 1800s in the U.S. as a parallel economic period. We had significant growth and a large trade deficit, consistent with heavy imports to fuel our rapidly-industrializing young nation. While Abe Lincoln was right about a lot of things, he was wrong to worry about trade deficits.

It goes without saying that this type of nuanced analysis will go over the heads of most U.S. Senators and Congressmen, and probably most Presidential candidates as well.

It reminds me of something my father used to frequently say. When listening to yet another media criticism of low voter turnouts in some fall election, he would remark thusly,

'Son, you only get to vote once every four years for the President. But you vote each day with your dollars, and those have a much larger and frequent impact than your political vote.'

What I think this means, pursuant to this post, is that, despite most politicians, and even most economists, not understanding the real dynamics of our trade deficit, so long as our nation's citizens just continue to drive our economy as usual, the trade deficit will not be any more of a problem in the future than it has in the past.

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Flawed Analytics and "Training Programs"

I recently discussed my post of last week concerning Home Depot with my partner. In it, I contrasted Lee Cooperman's cheery view of the company, in which his hedge fund has a sizable position, with the rather downbeat view of the firm, based simply upon its sales and NIAT numbers for the past five years. My partner and I wondered how such basic, obvious quantitative evidence could simply be ignored, and/or swept aside, by both Cooperman and Bartiromo.

He asked me if I thought Cooperman or Bartiromo even looked at HD's overall numbers? Or if I thought Bartiromo did anything more than simply reinforce, agree with, and mouth assent to Cooperman's selective factoids? On both counts, I admitted that I doubt it.

It would be one thing for this to occur in the course of private investment determinations. But to air such a shallow attempt at "analysis" on a major business medium such as CNBC seems to both observe the commonality of, and countenance, such shoddy work.

How much of this, do you suppose, goes on? Partial views of company performance? Selective factoid presentations? Skewed, biased 'analysis' in place of a clear presentation of information known to have a significant statistical relationship to the consistent attainment of superior total returns?

As we discussed the Cooperman-Bartiromo interview, we segued into a related matter- the ever-popular Wall Street two year 'training programs.' He wonders how anyone can really learn much of value, when worked to death like his son. A close friend and business associate of long standing also has a son who is about to enter one of these two-year prison camps. His son referred to it as "two years of hell."

I ask a different question,

'How can something which can be learned by anyone, in two short years, be of much lasting and unique value?' If so many go through these programs, how valuable can they be?'

Personally, I don't even think most MBAs learn all that much in two years.

First, consider that many, if not most, MBA candidates enter from non-business fields. So they spend the first year catching up to what a business undergrad spends his or her first two years learning. Then they interview for jobs beginning in the fall of the second year. Having landed an offer, their academic focus typically wanes. From my experience at a Top Five business school, I would estimate that the average MBA candidate actually focuses on learning anything considered 'advanced,' as opposed to simply passing basic courses or studying in their concentration area, for about six months.

Does this sound like a recipe for churning out unique, creative, value-adding managers?

Some years ago, I considered returning to my alma mater for a PhD in Marketing, the field in which I studied for my two business degrees. My former mentor and advisor took me to lunch at the Penn faculty club to discuss the idea. While we chatted, I observed that, in the decade or so since I had graduated with my MBA, leveraged buyouts and corporate restructurings had eviscerated almost, if not every, function and sector in corporate America. How could this have been emblematic of a corps of well-trained, competent, creative business grads making their productive and successful mark on the American business world?

He replied that, finally, at that time, circa 1990, MBAs were "finally" having an effect in the business world. Really? Only then?

Take the top five business school programs for the twenty-year period from 1970-90, and assume 500 members for each class. You get roughly 50,000 MBAs being disgorged into the US management ranks just from the top five B-schools alone.

No, I think most "two-year" programs, even for intelligent people, don't do much more than provide a rather common, universal business background. The Wall Street programs are more about finance, and less about real "business." The MBA programs seem to be a sort of business "boot camp" to winnow out the less capable, in order to provide a corps of semi-trained people eligible for further managerial 'training.'

My proprietary research has shown a remarkably stable average total return for the S&P500 over time. It does not seem to be the case that this influx of business school graduates or Wall Street trainees has enabled companies to return more to their shareholders.

Rather, I suspect that it simply provides a large pool of average managers to take their places in mostly non-high-value-adding positions in corporate America. Most of these graduates don't challenge what they've been taught, or even think much about it.

Where's the font of uniquely-skilled, creative, motivated business leaders who will make a difference for their shareholders? My guess is, they are rarely cut from the normal B-school or "training program" cloth. It's people with inspiration and ideas, not trained bean-counters and "managers," who will likely invigorate a company and earn its shareholders consistently superior total returns.

The good news, I guess, is that, as these "trained" robots continue to flood the financial markets, I have a sustained flow of similarly-thinking, non-creative counterparties with which to 'trade.'

He asked me if I thought Cooperman or Bartiromo even looked at HD's overall numbers? Or if I thought Bartiromo did anything more than simply reinforce, agree with, and mouth assent to Cooperman's selective factoids? On both counts, I admitted that I doubt it.

It would be one thing for this to occur in the course of private investment determinations. But to air such a shallow attempt at "analysis" on a major business medium such as CNBC seems to both observe the commonality of, and countenance, such shoddy work.

How much of this, do you suppose, goes on? Partial views of company performance? Selective factoid presentations? Skewed, biased 'analysis' in place of a clear presentation of information known to have a significant statistical relationship to the consistent attainment of superior total returns?

As we discussed the Cooperman-Bartiromo interview, we segued into a related matter- the ever-popular Wall Street two year 'training programs.' He wonders how anyone can really learn much of value, when worked to death like his son. A close friend and business associate of long standing also has a son who is about to enter one of these two-year prison camps. His son referred to it as "two years of hell."

I ask a different question,

'How can something which can be learned by anyone, in two short years, be of much lasting and unique value?' If so many go through these programs, how valuable can they be?'

Personally, I don't even think most MBAs learn all that much in two years.

First, consider that many, if not most, MBA candidates enter from non-business fields. So they spend the first year catching up to what a business undergrad spends his or her first two years learning. Then they interview for jobs beginning in the fall of the second year. Having landed an offer, their academic focus typically wanes. From my experience at a Top Five business school, I would estimate that the average MBA candidate actually focuses on learning anything considered 'advanced,' as opposed to simply passing basic courses or studying in their concentration area, for about six months.

Does this sound like a recipe for churning out unique, creative, value-adding managers?

Some years ago, I considered returning to my alma mater for a PhD in Marketing, the field in which I studied for my two business degrees. My former mentor and advisor took me to lunch at the Penn faculty club to discuss the idea. While we chatted, I observed that, in the decade or so since I had graduated with my MBA, leveraged buyouts and corporate restructurings had eviscerated almost, if not every, function and sector in corporate America. How could this have been emblematic of a corps of well-trained, competent, creative business grads making their productive and successful mark on the American business world?

He replied that, finally, at that time, circa 1990, MBAs were "finally" having an effect in the business world. Really? Only then?

Take the top five business school programs for the twenty-year period from 1970-90, and assume 500 members for each class. You get roughly 50,000 MBAs being disgorged into the US management ranks just from the top five B-schools alone.

No, I think most "two-year" programs, even for intelligent people, don't do much more than provide a rather common, universal business background. The Wall Street programs are more about finance, and less about real "business." The MBA programs seem to be a sort of business "boot camp" to winnow out the less capable, in order to provide a corps of semi-trained people eligible for further managerial 'training.'

My proprietary research has shown a remarkably stable average total return for the S&P500 over time. It does not seem to be the case that this influx of business school graduates or Wall Street trainees has enabled companies to return more to their shareholders.

Rather, I suspect that it simply provides a large pool of average managers to take their places in mostly non-high-value-adding positions in corporate America. Most of these graduates don't challenge what they've been taught, or even think much about it.

Where's the font of uniquely-skilled, creative, motivated business leaders who will make a difference for their shareholders? My guess is, they are rarely cut from the normal B-school or "training program" cloth. It's people with inspiration and ideas, not trained bean-counters and "managers," who will likely invigorate a company and earn its shareholders consistently superior total returns.

The good news, I guess, is that, as these "trained" robots continue to flood the financial markets, I have a sustained flow of similarly-thinking, non-creative counterparties with which to 'trade.'

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

CNBC's Erin Burnett's Myopia

This morning, on CNBC, Erin Burnett observed that the US equity markets posted nearly the smallest gains among the world's exchanges.

For example, she cited India's and Vietnam's markets as rising significantly more than that of the US, with Vietnam's up something like 45%.

Let's get something clear. All markets are not equal. For instance, Burnett doesn't mention liquidity, depth, trading expenses, or listing requirements. Little details, you know?

I find that this sort of 'shoot from the hip,' unconditioned observation, passing as analysis, is all too common on the network. Exactly who did this story help?

Institutional investors presumably already know about various international equity markets and their risks. Retail investors are typically advised to participate in markets via country-oriented mutual funds. Even there, reporting on this year's gains doesn't say anything about next year's. While this is always true, I would think it's especially true in thinner, less-well capitalized and transparent markets like those of third-world countries.

Once again, the network seems to deliver more on entertainment and less on hard, analytical business or markets news and analysis.

Investor beware, alright. Beware of the 'advice' you hear on CNBC.

For example, she cited India's and Vietnam's markets as rising significantly more than that of the US, with Vietnam's up something like 45%.

Let's get something clear. All markets are not equal. For instance, Burnett doesn't mention liquidity, depth, trading expenses, or listing requirements. Little details, you know?

I find that this sort of 'shoot from the hip,' unconditioned observation, passing as analysis, is all too common on the network. Exactly who did this story help?

Institutional investors presumably already know about various international equity markets and their risks. Retail investors are typically advised to participate in markets via country-oriented mutual funds. Even there, reporting on this year's gains doesn't say anything about next year's. While this is always true, I would think it's especially true in thinner, less-well capitalized and transparent markets like those of third-world countries.

Once again, the network seems to deliver more on entertainment and less on hard, analytical business or markets news and analysis.

Investor beware, alright. Beware of the 'advice' you hear on CNBC.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Indian Pharma Scientists Return Home

Last Thursday, the Wall Street Journal featured a piece on Indian scientists now returning to India. As with Chinese engineers, many of the scientists have formerly been with large American firms- in this case, pharmaceuticals.

On the whole, though, I believe it's a good thing. India becomes more wired into global trade, as its scientists begin to develop new medicines and seek to export them. It will open India up, much as the evolving economy of China will for that country.

In time, Indian pharma wages will rise, and even it will gradually become less competitive, on a comparative basis. Of course, as more Indian professionals return and start competing firms in technology, pharmaceuticals, commodities, etc, their standards of living will rise, and they will consume more international goods and services. Many, no doubt, will be American in origin.

Perhaps, over the next decade, Western firms will begin to acquire some of these Indian startups, in the same way they often buy ideas and talent in the US that left the paralysis of large corporations, to start new businesses. We don't yet know what India will adopt as a policy involving this sort of acquisition activity, but it may well become more important for world trade in the coming years. Will Western countries and markets remain open to Indian and Chinese markets that constrict asset purchases, ownership, and economic participation by foreign companies?

How will a Democratic US Congress view the loss of higher-paying, management jobs to countries such as India? Especially if the latter maintains trade barriers, while attempting to export newly-developed products and services?

This is free trade. Isn't this what we, as Americans, ultimately want? Comparative advantage and mobility work. If this is what it takes to re-energize some sectors of large corporate America, as it sees an ethnic brain drain, so be it.

The migration of highly-educated talent back to home countries may, on one hand, look like a net loss for America. However, it may well result, as in China, in the accelerated Westernization of these formerly-third-world countries, so that their economic, social and political values and agendas begin to more closely resemble those of America and her Western allies. As we move further into what promises to be a long global war on terror, initiated by radical elements of Islam, can it be a bad thing to have the world's two most populous nations begin to adopt America's perspectives on economic growth, development, and living standards?

Rather than see a brain drain, perhaps we should view developments such as the Indian scientists returning home as a net loss to the US, perhaps we should see it as successful export of, and prostyletizing on behalf of, our values and socio-economic system. Much cheaper, and more effective, than military conquest of foreign lands. This way, our economic system becomes embedded into other cultures, and fosters nascent democratic political appetites, as well.

On the whole, though, I believe it's a good thing. India becomes more wired into global trade, as its scientists begin to develop new medicines and seek to export them. It will open India up, much as the evolving economy of China will for that country.

In time, Indian pharma wages will rise, and even it will gradually become less competitive, on a comparative basis. Of course, as more Indian professionals return and start competing firms in technology, pharmaceuticals, commodities, etc, their standards of living will rise, and they will consume more international goods and services. Many, no doubt, will be American in origin.

Perhaps, over the next decade, Western firms will begin to acquire some of these Indian startups, in the same way they often buy ideas and talent in the US that left the paralysis of large corporations, to start new businesses. We don't yet know what India will adopt as a policy involving this sort of acquisition activity, but it may well become more important for world trade in the coming years. Will Western countries and markets remain open to Indian and Chinese markets that constrict asset purchases, ownership, and economic participation by foreign companies?

How will a Democratic US Congress view the loss of higher-paying, management jobs to countries such as India? Especially if the latter maintains trade barriers, while attempting to export newly-developed products and services?

This is free trade. Isn't this what we, as Americans, ultimately want? Comparative advantage and mobility work. If this is what it takes to re-energize some sectors of large corporate America, as it sees an ethnic brain drain, so be it.

The migration of highly-educated talent back to home countries may, on one hand, look like a net loss for America. However, it may well result, as in China, in the accelerated Westernization of these formerly-third-world countries, so that their economic, social and political values and agendas begin to more closely resemble those of America and her Western allies. As we move further into what promises to be a long global war on terror, initiated by radical elements of Islam, can it be a bad thing to have the world's two most populous nations begin to adopt America's perspectives on economic growth, development, and living standards?

Rather than see a brain drain, perhaps we should view developments such as the Indian scientists returning home as a net loss to the US, perhaps we should see it as successful export of, and prostyletizing on behalf of, our values and socio-economic system. Much cheaper, and more effective, than military conquest of foreign lands. This way, our economic system becomes embedded into other cultures, and fosters nascent democratic political appetites, as well.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Home Depot, Again: Leon Cooperman's "Powerful Numbers"

Yesterday afternoon, Maria Bartiromo interviewed Omega Fund founder CEO, Leon Cooperman, by telephone, on CNBC. The "video," with Cooperman's audio, can be viewed here.

I must admit that I found the 'interview' to be rather unusual. Rather than have Cooperman interact, on camera or via microphones, with one Ralph Whitworth, another institutional investor who is assailing Home Depot's board and management for ineptitude, Bartiromo/CNBC chose to simply refer to Whitworth, show a video clip of an earlier interview with him, and then present Cooperman live, alone. She opened the piece by citing Omega's 5 1/4 B of assets under management, and its position of 2.5MM shares of HD. The nature of the introduction seemed calculated to confer some sort of infallibility on Cooperman and his investing choices.

Could Lee be 'pumping' Home Depot, with CNBC's help? Or, at the least, defending it?

Let me be very clear here. I am not saying that Cooperman, Bartiromo, or CNBC did anything illegal. Omega's beneficial interest in Home Depot was explicitly stated at the beginning of the interview. However, it is indisputable that CNBC had Cooperman appear in order to tout a stock in which his fund has a fairly large position. Further, they had him on after another investor who had made pointed allegations of board and managerial failures to perform.

Cooperman went on to list a set of reasons to risk your capital on HD. He gave testimonials on Nardelli, via Jack Welch, Nardelli's one-time manager at GE, on Welch himself, and on two directors of HD. Fine. But, where's the beef?

Maria said, in agreement with Cooperman, of Nardelli's operating record,

"the numbers are powerful....revenues, earnings.....powerful under Nardelli....no doubt about it."

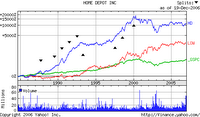

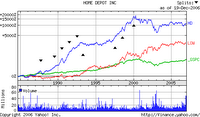

Really? Look at the chart on the left, displaying the performance of sales, NIAT, and total return for Home Depot and Lowes since 2000. You may click on the chart, and on the subsequent stock price charts, to view larger versions of all of them.

Really? Look at the chart on the left, displaying the performance of sales, NIAT, and total return for Home Depot and Lowes since 2000. You may click on the chart, and on the subsequent stock price charts, to view larger versions of all of them.

Sales growth has finally accelerated again at HD in the last twelve months, but it still lags that of its major competitor, Lowes. Net Income Available after Taxes, up 9% for the past twelve months, is the lowest increase since the first full year under Nardelli. And, again, it lags Lowes by more than twofold.

Powerful performance, eh, Bob...Maria....Lee? I just don't see it. I didn't see it, here, or here, either, in my posts on this topic back in July of this year.

Cooperman went on to list a series of rapid-fire 'data' about Home Depot. Its real estate position has increased. Dividends and earnings up over a short period of time. The company bought stock back. So what? These are intermediate activities which are not having an effect on the firm's stock price. That Lee Cooperman thinks they should is beside the point, isn't it? Unless his personal opinion is supposed to be sufficient reason to buy the stock. Which would be nice for him, since his fund, remember, already owns 2.5MM shares of Home Depot.

Cooperman clearly believes, as a result of his fund's analytical team's meetings with HD's management, that the company's stock will eventually be appreciated, even though, now, it's "undervalued." His reeling off of the many operating statistics, mostly rather abstruse numbers, sounded like he was reading from a list his analysts had prepared for him.

Specifically, it reminds me of my own experiences in corporate America. The staffers build a set of numbers and talking points so that the senior executive, who is not as well-versed on the topic, can rattle off seemingly-unassailable numbers. Do you think any of the carefully-selected data presented by Cooperman, on behalf of his analysts, will be negative or cast doubt on Home Depot's 'powerful' operating results? Unlikely.

To get a better picture, here's a Yahoo-sourced chart of stock prices for Home Depot and Lowes, plus the S&P500 Index, for the past five years. Lowes is clearly superior, and HD can't even outperform the S&P. Despite Cooperman's plea that the firm is simply misunderstood, the market

To get a better picture, here's a Yahoo-sourced chart of stock prices for Home Depot and Lowes, plus the S&P500 Index, for the past five years. Lowes is clearly superior, and HD can't even outperform the S&P. Despite Cooperman's plea that the firm is simply misunderstood, the market

For a little more perspective, here's a chart of the same data for a much longer timeframe. It's clear that, since 2000, things have never been as good for Home Depot as they were before then. Nothing that Nardelli has done for six years has succeeded in improving the company's total return to beat that of the S&P500.

For a little more perspective, here's a chart of the same data for a much longer timeframe. It's clear that, since 2000, things have never been as good for Home Depot as they were before then. Nothing that Nardelli has done for six years has succeeded in improving the company's total return to beat that of the S&P500.

Meanwhile, Lowes' stock price has continued to rise steadily, though not, apparently, much faster than the index since around 2001.

The only basis on which I saw improvement in HD's stock was in the last three months. Blogger is not cooperating with my attempts to paste a stock price chart. However, Yahoo's charts shows that, over the past 90 days, HD has outperformed Lowes, roughly 9% vs. flat, but still underperformed the S&P.

Of course, if Cooperman's premise is that you have to catch the right 3-6 month period in order to earn superior returns in Home Depot, I don't think that's going to help most investors. It sounds more like investing on technical indicators, and hopes of a short-term "pop" from some transitory fundamentals in the near future, then correctly timing your exit from the position.

However, in terms of long-term, consistent performance, Home Depot does not appear to have improved since my analysis in July of this year. And, on a comparative basis, it does not seem to be performing "powerfully" at all, Maria Bartiromo's and Leon Cooperman's contentions to the contrary. I attempt to present the data on which I base my assessments whenever I critique a company's performance. For me, the Cooperman interview on CNBC, and Bartiromo's and Cooperman's statements claiming great fundamental performance for Home Depot, seem empty without clear, written or graphic evidence to substantiate them.

I must admit that I found the 'interview' to be rather unusual. Rather than have Cooperman interact, on camera or via microphones, with one Ralph Whitworth, another institutional investor who is assailing Home Depot's board and management for ineptitude, Bartiromo/CNBC chose to simply refer to Whitworth, show a video clip of an earlier interview with him, and then present Cooperman live, alone. She opened the piece by citing Omega's 5 1/4 B of assets under management, and its position of 2.5MM shares of HD. The nature of the introduction seemed calculated to confer some sort of infallibility on Cooperman and his investing choices.

Could Lee be 'pumping' Home Depot, with CNBC's help? Or, at the least, defending it?

Let me be very clear here. I am not saying that Cooperman, Bartiromo, or CNBC did anything illegal. Omega's beneficial interest in Home Depot was explicitly stated at the beginning of the interview. However, it is indisputable that CNBC had Cooperman appear in order to tout a stock in which his fund has a fairly large position. Further, they had him on after another investor who had made pointed allegations of board and managerial failures to perform.

Cooperman went on to list a set of reasons to risk your capital on HD. He gave testimonials on Nardelli, via Jack Welch, Nardelli's one-time manager at GE, on Welch himself, and on two directors of HD. Fine. But, where's the beef?

Maria said, in agreement with Cooperman, of Nardelli's operating record,

"the numbers are powerful....revenues, earnings.....powerful under Nardelli....no doubt about it."

Really? Look at the chart on the left, displaying the performance of sales, NIAT, and total return for Home Depot and Lowes since 2000. You may click on the chart, and on the subsequent stock price charts, to view larger versions of all of them.

Really? Look at the chart on the left, displaying the performance of sales, NIAT, and total return for Home Depot and Lowes since 2000. You may click on the chart, and on the subsequent stock price charts, to view larger versions of all of them.Sales growth has finally accelerated again at HD in the last twelve months, but it still lags that of its major competitor, Lowes. Net Income Available after Taxes, up 9% for the past twelve months, is the lowest increase since the first full year under Nardelli. And, again, it lags Lowes by more than twofold.

Powerful performance, eh, Bob...Maria....Lee? I just don't see it. I didn't see it, here, or here, either, in my posts on this topic back in July of this year.

Cooperman went on to list a series of rapid-fire 'data' about Home Depot. Its real estate position has increased. Dividends and earnings up over a short period of time. The company bought stock back. So what? These are intermediate activities which are not having an effect on the firm's stock price. That Lee Cooperman thinks they should is beside the point, isn't it? Unless his personal opinion is supposed to be sufficient reason to buy the stock. Which would be nice for him, since his fund, remember, already owns 2.5MM shares of Home Depot.

Cooperman clearly believes, as a result of his fund's analytical team's meetings with HD's management, that the company's stock will eventually be appreciated, even though, now, it's "undervalued." His reeling off of the many operating statistics, mostly rather abstruse numbers, sounded like he was reading from a list his analysts had prepared for him.

Specifically, it reminds me of my own experiences in corporate America. The staffers build a set of numbers and talking points so that the senior executive, who is not as well-versed on the topic, can rattle off seemingly-unassailable numbers. Do you think any of the carefully-selected data presented by Cooperman, on behalf of his analysts, will be negative or cast doubt on Home Depot's 'powerful' operating results? Unlikely.

To get a better picture, here's a Yahoo-sourced chart of stock prices for Home Depot and Lowes, plus the S&P500 Index, for the past five years. Lowes is clearly superior, and HD can't even outperform the S&P. Despite Cooperman's plea that the firm is simply misunderstood, the market

To get a better picture, here's a Yahoo-sourced chart of stock prices for Home Depot and Lowes, plus the S&P500 Index, for the past five years. Lowes is clearly superior, and HD can't even outperform the S&P. Despite Cooperman's plea that the firm is simply misunderstood, the market For a little more perspective, here's a chart of the same data for a much longer timeframe. It's clear that, since 2000, things have never been as good for Home Depot as they were before then. Nothing that Nardelli has done for six years has succeeded in improving the company's total return to beat that of the S&P500.

For a little more perspective, here's a chart of the same data for a much longer timeframe. It's clear that, since 2000, things have never been as good for Home Depot as they were before then. Nothing that Nardelli has done for six years has succeeded in improving the company's total return to beat that of the S&P500.Meanwhile, Lowes' stock price has continued to rise steadily, though not, apparently, much faster than the index since around 2001.

The only basis on which I saw improvement in HD's stock was in the last three months. Blogger is not cooperating with my attempts to paste a stock price chart. However, Yahoo's charts shows that, over the past 90 days, HD has outperformed Lowes, roughly 9% vs. flat, but still underperformed the S&P.

Of course, if Cooperman's premise is that you have to catch the right 3-6 month period in order to earn superior returns in Home Depot, I don't think that's going to help most investors. It sounds more like investing on technical indicators, and hopes of a short-term "pop" from some transitory fundamentals in the near future, then correctly timing your exit from the position.

However, in terms of long-term, consistent performance, Home Depot does not appear to have improved since my analysis in July of this year. And, on a comparative basis, it does not seem to be performing "powerfully" at all, Maria Bartiromo's and Leon Cooperman's contentions to the contrary. I attempt to present the data on which I base my assessments whenever I critique a company's performance. For me, the Cooperman interview on CNBC, and Bartiromo's and Cooperman's statements claiming great fundamental performance for Home Depot, seem empty without clear, written or graphic evidence to substantiate them.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Income Inequality

Alan Reynolds wrote a fabulous piece in the Wall Street Journal last Thursday concerning America's alleged income inequality. It is a masterpiece in demonstrating that attention to details, and knowledge of data sources, can make all the difference between a valid conclusion, and useless speculation.

Specifically, Reynolds, who is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and co-founder of Polyconomics, identifies the source of Senatorial candidate Jim Webb's statement that,

"the top 1% now takes in an astounding 16% of national income, up from 8% in 1980."

The researchers responsible for these numbers, Thomas Piketty, of Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris, and Emmanuel Saez, of the University of California at Berkeley, used tax returns for their denominator, rather than total income. Major income sources which they omitted, according to Reynolds, were Social Security and other transfer payments. Of course, we would expect these types of payments to go to lower income earners, thus further skewing the findings of the two researchers.

Other sources of error include the non-filing of some income earners, municipal bond and other tax-exempt income sources, and the inclusion of two, joint filers on single tax returns at the higher end of the tax-reported income spectrum. Reynolds estimates that total personal incomes, the denominator for the inequality statistics, was roughly $3.3B in 2004, or slightly more than 1/3 larger than Piketty and Saez estimated.

Another source of error which Reynolds discusses is the tax-policy-driven shift of small, formerly conventionally-filing corporations, to Subchapter S corporations. These are often higher income sources taking advantage of a different reporting structure, thus improperly appearing to inflate upper incomes, when, in reality, they were simply measured as business income sources in prior years.

Reynolds' fine, detailed and sensible work demonstrates how easily such inflammatory statistics as the ones Senator-elect Webb (D-Va) used can become commonly held "wisdom," or "fact."

In reality, it appears that the work on which those statistics are based was very flawed, and has generated suspect results. As time-consuming, dry and tedious as it may be, doing the fundamental work of investigating definitions and research methodologies can often shed valuable, and, occasionally, disconfirming light on apparently important and troubling results. Such is the case with the now-well-publicized 'increasing income inequality' in America, as demonstrated by Alan Reynold's good work and articulate explanations.

Specifically, Reynolds, who is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and co-founder of Polyconomics, identifies the source of Senatorial candidate Jim Webb's statement that,

"the top 1% now takes in an astounding 16% of national income, up from 8% in 1980."

The researchers responsible for these numbers, Thomas Piketty, of Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris, and Emmanuel Saez, of the University of California at Berkeley, used tax returns for their denominator, rather than total income. Major income sources which they omitted, according to Reynolds, were Social Security and other transfer payments. Of course, we would expect these types of payments to go to lower income earners, thus further skewing the findings of the two researchers.

Other sources of error include the non-filing of some income earners, municipal bond and other tax-exempt income sources, and the inclusion of two, joint filers on single tax returns at the higher end of the tax-reported income spectrum. Reynolds estimates that total personal incomes, the denominator for the inequality statistics, was roughly $3.3B in 2004, or slightly more than 1/3 larger than Piketty and Saez estimated.

Another source of error which Reynolds discusses is the tax-policy-driven shift of small, formerly conventionally-filing corporations, to Subchapter S corporations. These are often higher income sources taking advantage of a different reporting structure, thus improperly appearing to inflate upper incomes, when, in reality, they were simply measured as business income sources in prior years.

Reynolds' fine, detailed and sensible work demonstrates how easily such inflammatory statistics as the ones Senator-elect Webb (D-Va) used can become commonly held "wisdom," or "fact."

In reality, it appears that the work on which those statistics are based was very flawed, and has generated suspect results. As time-consuming, dry and tedious as it may be, doing the fundamental work of investigating definitions and research methodologies can often shed valuable, and, occasionally, disconfirming light on apparently important and troubling results. Such is the case with the now-well-publicized 'increasing income inequality' in America, as demonstrated by Alan Reynold's good work and articulate explanations.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Toyota's Awesome Drive To Dominance

Last (December 10th) weekend's Wall Street Journal featured an article about Toyota. Having a series of more timely pieces which occurred last week, I elected to wait until now to accord this post the attention it deserves. There are several important insights to be gleaned from the Journal article concerning my research and thoughts about consistently superior performance. Toyota is showing both the good and the bad effects of consistently superior performance- how to do it, what it returns, how fragile and fleeting it can be.

What initially struck me from the Journal piece is how Toyota CEO Katsuaki Watanbe's incredible insecurity fuels his company's continued excellent performance.

What initially struck me from the Journal piece is how Toyota CEO Katsuaki Watanbe's incredible insecurity fuels his company's continued excellent performance.

As the nearby, Yahoo-sourced chart of Toyota's stock price, versus the S&P500 Index, indicates, the company has performed consistently better than the latter for most of the past five years. It's cumulative total return far surpasses that of the index over the entire period. Toyota isn't among the companies in the S&P500, so I don't own it. How I wish I could, and did.

As my proprietary research warns, however, cost-cutting is a relatively limited weapon in the quest for long-term, consistently superior total returns. Toyota's are already nearing an end as a competitive weapon. The rate of cost reductions is slowing, and product design flaws have recently spurred recalls of more vehicles than it sold last year.

I was very impressed with the attention to detail by the CEO. The Journal article discusses his observant manner as he walks the floor of his plants. His questioning of the traditional, long paint shop river, is what recently has led to Toyota's secret new process, which takes far less space and resources. Watanabe is ceaselessly exploring new ways to drive costs down and extend Toyota's lead in this area. To this end, he has commissioned a total re-evaluation of the production of the company's vehicles, with an audacious objective of cutting the number of parts required by 50%.

While, on one hand, Toyota is bumping up against some cost-cutting limits of current production methods, Watanabe is wisely opening up the company's managers to exploring entirely new ways of designing and producing their vehicles, thus, effectively, in microeconomics terms, putting the firm's operations on a new, longer-term, declining cost curve. They have redesigned their machines to be smaller, and their plants as well.

What amazes me about Toyota is that, while GM is catching up to them in some production efficiency measures in some plants, Toyota is already moving to tackle new production challenges that I cannot even imagine GM being ready to address. The production plant challenge is one, as is the paint line. Thus, Toyota is working on changing the very methods by which they will more efficiently pump out vehicles, while GM, and, presumably, Ford, are still working on making existing methods merely more efficient. It's clear that the two American auto giants are not even remotely in the same class as Toyota when it comes to conceiving and implementing continuous methods of improving operating efficiencies, and, thus, value-added.

Will Toyota succeed in these operational changes? Their diminishing lead in current efficiencies demonstrates how cost leadership can shrink, and, thus, lead to a loss of sustained superior performance. However, they are attempting new initiatives to retain this consistently superior total return performance. Either way, they are at risk.

And this, I believe, is one of the most enlightening elements of the Journal's Toyota story. Even a detail- and big-picture-obsessed, experienced and successful CEO, like Watanable, with a willing workforce, and strong competitive position, cannot count on continued superior total return performance. He's betting the company's continued performance every year, with each new initiative.

Sooner or later, Toyota will run into more difficulties in one of its programs for new production methods, or design flaws, that will derail its superb performance of the past few years. The truth is, with each additional year of excellent performance, their odds of another one diminish. It's simply how performance patterns are among large numbers of large corporations.

However, I will take great interest in seeing for how long this impressive auto producer can maintain its record of consistently outperforming the S&P500's total return.

What initially struck me from the Journal piece is how Toyota CEO Katsuaki Watanbe's incredible insecurity fuels his company's continued excellent performance.

What initially struck me from the Journal piece is how Toyota CEO Katsuaki Watanbe's incredible insecurity fuels his company's continued excellent performance.As the nearby, Yahoo-sourced chart of Toyota's stock price, versus the S&P500 Index, indicates, the company has performed consistently better than the latter for most of the past five years. It's cumulative total return far surpasses that of the index over the entire period. Toyota isn't among the companies in the S&P500, so I don't own it. How I wish I could, and did.

As my proprietary research warns, however, cost-cutting is a relatively limited weapon in the quest for long-term, consistently superior total returns. Toyota's are already nearing an end as a competitive weapon. The rate of cost reductions is slowing, and product design flaws have recently spurred recalls of more vehicles than it sold last year.

I was very impressed with the attention to detail by the CEO. The Journal article discusses his observant manner as he walks the floor of his plants. His questioning of the traditional, long paint shop river, is what recently has led to Toyota's secret new process, which takes far less space and resources. Watanabe is ceaselessly exploring new ways to drive costs down and extend Toyota's lead in this area. To this end, he has commissioned a total re-evaluation of the production of the company's vehicles, with an audacious objective of cutting the number of parts required by 50%.

While, on one hand, Toyota is bumping up against some cost-cutting limits of current production methods, Watanabe is wisely opening up the company's managers to exploring entirely new ways of designing and producing their vehicles, thus, effectively, in microeconomics terms, putting the firm's operations on a new, longer-term, declining cost curve. They have redesigned their machines to be smaller, and their plants as well.

What amazes me about Toyota is that, while GM is catching up to them in some production efficiency measures in some plants, Toyota is already moving to tackle new production challenges that I cannot even imagine GM being ready to address. The production plant challenge is one, as is the paint line. Thus, Toyota is working on changing the very methods by which they will more efficiently pump out vehicles, while GM, and, presumably, Ford, are still working on making existing methods merely more efficient. It's clear that the two American auto giants are not even remotely in the same class as Toyota when it comes to conceiving and implementing continuous methods of improving operating efficiencies, and, thus, value-added.

Will Toyota succeed in these operational changes? Their diminishing lead in current efficiencies demonstrates how cost leadership can shrink, and, thus, lead to a loss of sustained superior performance. However, they are attempting new initiatives to retain this consistently superior total return performance. Either way, they are at risk.

And this, I believe, is one of the most enlightening elements of the Journal's Toyota story. Even a detail- and big-picture-obsessed, experienced and successful CEO, like Watanable, with a willing workforce, and strong competitive position, cannot count on continued superior total return performance. He's betting the company's continued performance every year, with each new initiative.

Sooner or later, Toyota will run into more difficulties in one of its programs for new production methods, or design flaws, that will derail its superb performance of the past few years. The truth is, with each additional year of excellent performance, their odds of another one diminish. It's simply how performance patterns are among large numbers of large corporations.

However, I will take great interest in seeing for how long this impressive auto producer can maintain its record of consistently outperforming the S&P500's total return.

Wal-Mart Employee Attacks Customer

It's true that sometimes, only one rotten apple is necessary to spoil the whole barrel. As rational adults, on one level, we know this to mean that we shouldn't judge an entire organization by the actions of a single member.

Still, with all the outrage and angst Wal-Mart has generated this year, much of it self-inflicted, this episode, occurring at a Wal-Mart store in Gainesville, Florida, is hardly what Lee Scott needed to read about on this pre-Christmas holiday weekend. My consulting friend S sent me this link to the following story.......

Woman Slashed At Gainesville Wal-Mart 12/17/2006 By Michael Maurino

WCJB TV-20 News

One local teen went to a store to go shopping and ended up taking a trip to the hospital after a fight with an employee.

Now the store employee is facing jail time after slashing her across the neck.

Gainesville Police say the 17-year-old teenage girl was visiting the Wal-Mart on Northwest 13th Street.

She had walked out of the store, but went back when she thought she left her cell phone in a shopping cart.

Detectives say she approached 18-year-old Wal-Mart employee Darius stacy, who was retreving the carts, and asked if he had the phone.

The two started arguing, and then shoving each other before Stacy pulled out a weapon.

"The employee had a box cutter and he cut the 17 year old in the throat," said GPD Sgt. Keith Kameg. "Fortunately, they were non life threatening injures."

The young woman was treated at Shands U-F for a cut that extended from her left ear to her windpipe.

Stacy is being charged with attempted murder.

Need we mention something about every employee being a 'goodwill' ambassador? It's pretty rough when you now have to worry about contact with even the cart handlers at the nation's largest retailer.

Certainly it argues for online shopping, does it not?

Still, with all the outrage and angst Wal-Mart has generated this year, much of it self-inflicted, this episode, occurring at a Wal-Mart store in Gainesville, Florida, is hardly what Lee Scott needed to read about on this pre-Christmas holiday weekend. My consulting friend S sent me this link to the following story.......

Woman Slashed At Gainesville Wal-Mart 12/17/2006 By Michael Maurino

WCJB TV-20 News

One local teen went to a store to go shopping and ended up taking a trip to the hospital after a fight with an employee.

Now the store employee is facing jail time after slashing her across the neck.

Gainesville Police say the 17-year-old teenage girl was visiting the Wal-Mart on Northwest 13th Street.

She had walked out of the store, but went back when she thought she left her cell phone in a shopping cart.

Detectives say she approached 18-year-old Wal-Mart employee Darius stacy, who was retreving the carts, and asked if he had the phone.

The two started arguing, and then shoving each other before Stacy pulled out a weapon.

"The employee had a box cutter and he cut the 17 year old in the throat," said GPD Sgt. Keith Kameg. "Fortunately, they were non life threatening injures."

The young woman was treated at Shands U-F for a cut that extended from her left ear to her windpipe.

Stacy is being charged with attempted murder.

Need we mention something about every employee being a 'goodwill' ambassador? It's pretty rough when you now have to worry about contact with even the cart handlers at the nation's largest retailer.

Certainly it argues for online shopping, does it not?

Friday, December 15, 2006

It's Different for CEOs: Chuck Prince's Four Year Probationary Period

Lest you think corporate America has become too hard on employees....too unforgiving and impatient......consider its treatment of one Charles Prince. I'm referring to CitiGroup CEO/Chairman Chuck Prince, of course.

In this post, late last month, I discussed CitiGroup's situation vis a vis BofA. Many media pundits were all a-twitter that the latter was about, and apparently did, overtake the former in terms of market value.

However, as I pointed out in that piece, the important measure to observe is consistent total return. In the charts contained in that post, you will see how Prince has steered CitiGroup into a dead-calm pool of a virtually flat, that is to say, zero, total return for his tenure as the firm's CEO and Chairman.

Now, such dismal performance might, you would think, merit dismissal. How many line VPs or SVPs of a major money-center bank would still be in their jobs, if they failed, for three straight years, to achieve their objectives? While their competitors outperformed them?

Not many, I'd wager. But, it's different for CEOs. First, they get paid a lot more, regardless of their inadequate performance for years at a time.

Mr. Prince's FY2005 compensation is detailed here, courtesy of Forbes Magazine. According to Forbes, with confirming information from Reuters, here, Prince was paid roughly $13MM in 'direct,' cash-like compensation last year, and an additional $10MM in various options and longer-term compensation.

Second, CEOs get a lot more time to perform. Prince has been CEO at CitiGroup for three years, and COO for two years prior to that. Word was, after the company's recent analysts meeting this week, that Prince has 'only another year' to 'fix things.'

Wow, that's pressure, eh? Only four years, at something north of $13MM cash compensation per year, to mismanage one of the nation's largest banks.

Where does the line form to replace him, come next January?

The way I figure it, with Prince's lack of operating background, and four-year record of failure, the requirements for the job should be pretty minimal. Nearly anyone, apparently, can satisfy Citi's board as competent to lead the banking firm.

Wouldn't you volunteer to risk your career in order to get a shot at $50-100MM in total compensation over four years, knowing termination after year four is the penalty?

Life at the top is tough, friends.....very, very tough indeed.

NOT!

In this post, late last month, I discussed CitiGroup's situation vis a vis BofA. Many media pundits were all a-twitter that the latter was about, and apparently did, overtake the former in terms of market value.

However, as I pointed out in that piece, the important measure to observe is consistent total return. In the charts contained in that post, you will see how Prince has steered CitiGroup into a dead-calm pool of a virtually flat, that is to say, zero, total return for his tenure as the firm's CEO and Chairman.

Now, such dismal performance might, you would think, merit dismissal. How many line VPs or SVPs of a major money-center bank would still be in their jobs, if they failed, for three straight years, to achieve their objectives? While their competitors outperformed them?

Not many, I'd wager. But, it's different for CEOs. First, they get paid a lot more, regardless of their inadequate performance for years at a time.

Mr. Prince's FY2005 compensation is detailed here, courtesy of Forbes Magazine. According to Forbes, with confirming information from Reuters, here, Prince was paid roughly $13MM in 'direct,' cash-like compensation last year, and an additional $10MM in various options and longer-term compensation.

Second, CEOs get a lot more time to perform. Prince has been CEO at CitiGroup for three years, and COO for two years prior to that. Word was, after the company's recent analysts meeting this week, that Prince has 'only another year' to 'fix things.'

Wow, that's pressure, eh? Only four years, at something north of $13MM cash compensation per year, to mismanage one of the nation's largest banks.

Where does the line form to replace him, come next January?

The way I figure it, with Prince's lack of operating background, and four-year record of failure, the requirements for the job should be pretty minimal. Nearly anyone, apparently, can satisfy Citi's board as competent to lead the banking firm.

Wouldn't you volunteer to risk your career in order to get a shot at $50-100MM in total compensation over four years, knowing termination after year four is the penalty?

Life at the top is tough, friends.....very, very tough indeed.

NOT!

Thursday, December 14, 2006

David Geffen's Bad News for Hank Greenberg, Jack Welch & Co. : It's Not About The Money

Two weeks ago, I wrote this post regarding Hank Greenberg's activity in pursuit of the New York Times Company. In that piece, I noted Jack Welch's pursuit, with a group of other investors, of the Boston Globe.

Now comes some bad news from a seriously creative, wealthy businessman. In last Friday's Wall Street Journal's article about him, Geffen admitted to wanting to build "a pre-eminent newspaper."

Further, he is quoted in the article as saying,

"It's difficult starting a business from scratch....The next thing I do, I want to buy rather than start from scratch....As a guy who is committed to, certainly by the time I die, giving everything I have a way, that gives me an awful lot of latitude about what I can and can't do."

According to Forbes' 2005 survey, Mr. Geffen is ranked #117 on the list of the world's richest people, with a net worth of approximately $4.4B. Hank Greenberg was #170, with an estimated net worth of $3.2B. That may now overstate Greenberg's net worth, as his resignation from AIG in mid-2005 may have resulted in his loss of significant assets. Jack Welch was #376, with an estimated net worth of $680MM, as of the Forbes 2001 survey, but is no longer on the list in 2005. Perhaps the result of his expensive, very public divorce from his second wife earlier in this decade.

Viewed from this perspective, Geffen has the deepest pockets, with Greenberg coming next. While Welch and his syndicate can doubtless borrow to buy the Boston Globe from the New York Times, Greenberg's interest in the parent may complicate, or may simplify, their pursuit of the ailing newspaper.

It's perhaps noteworthy that Geffen, somewhat an impressario of artistic talent, created the largest economic fortune of the three. Less of a classic businessman than the other two, his objective of building a "pre-eminent" newspaper should probably be chilling news to Greenberg and Welch. Geffen clearly has no compunction about pouring as much of his net worth into the effort as necessary.

I doubt Welch is that altruistic. Given Greenberg's maneuvering vis a vis his financial interests in AIG, I think he's more like Welch than he is like Geffen. For either of these former corporate types, with their smaller kitties, to engage in new-era newspaper-building combat with Geffen might well lead to their financial ruin.

Geffen's comments can't be good news for Welch. What will the lenders at (JP Morgan) Chase, to whom Welch has gone for financing, now think about bankrolling the least-well-funded entrant in a game in which the best-funded player has already announced he's willing to lose it all to reach his objective? Given Geffen's rather iconoclastic approaches to his work, he may well have some innovative ideas for reviving newspapers that the other two ex-CEOs can't even imagine.

This will be an interesting area to watch in 2007.

Now comes some bad news from a seriously creative, wealthy businessman. In last Friday's Wall Street Journal's article about him, Geffen admitted to wanting to build "a pre-eminent newspaper."

Further, he is quoted in the article as saying,

"It's difficult starting a business from scratch....The next thing I do, I want to buy rather than start from scratch....As a guy who is committed to, certainly by the time I die, giving everything I have a way, that gives me an awful lot of latitude about what I can and can't do."

According to Forbes' 2005 survey, Mr. Geffen is ranked #117 on the list of the world's richest people, with a net worth of approximately $4.4B. Hank Greenberg was #170, with an estimated net worth of $3.2B. That may now overstate Greenberg's net worth, as his resignation from AIG in mid-2005 may have resulted in his loss of significant assets. Jack Welch was #376, with an estimated net worth of $680MM, as of the Forbes 2001 survey, but is no longer on the list in 2005. Perhaps the result of his expensive, very public divorce from his second wife earlier in this decade.

Viewed from this perspective, Geffen has the deepest pockets, with Greenberg coming next. While Welch and his syndicate can doubtless borrow to buy the Boston Globe from the New York Times, Greenberg's interest in the parent may complicate, or may simplify, their pursuit of the ailing newspaper.

It's perhaps noteworthy that Geffen, somewhat an impressario of artistic talent, created the largest economic fortune of the three. Less of a classic businessman than the other two, his objective of building a "pre-eminent" newspaper should probably be chilling news to Greenberg and Welch. Geffen clearly has no compunction about pouring as much of his net worth into the effort as necessary.

I doubt Welch is that altruistic. Given Greenberg's maneuvering vis a vis his financial interests in AIG, I think he's more like Welch than he is like Geffen. For either of these former corporate types, with their smaller kitties, to engage in new-era newspaper-building combat with Geffen might well lead to their financial ruin.

Geffen's comments can't be good news for Welch. What will the lenders at (JP Morgan) Chase, to whom Welch has gone for financing, now think about bankrolling the least-well-funded entrant in a game in which the best-funded player has already announced he's willing to lose it all to reach his objective? Given Geffen's rather iconoclastic approaches to his work, he may well have some innovative ideas for reviving newspapers that the other two ex-CEOs can't even imagine.

This will be an interesting area to watch in 2007.

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

GE's Immelt: Still Underperforming and Still Making Excuses

The video of this morning's appearance by GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt on CNBC can be viewed here .

It runs about 8+ minutes. However, of particular interest to me was the segment at roughly minute 4:30 into the interview. This is where Joe Kernen of CNBC's Squawk Box program, asks Immelt, his ultimate boss, about why GE, as a conglomerate, is valuable.

Immelt rather brazenly says that GE exists 'because the market lets it exist,' or something like that. You can hear the exact quote for yourself at the video link. In defending the conglomeration, Immelt mentions, "performance" and 'common culture, goals....'

Then, to deflect attention from his own failure as CEO to beat the S&P, he now espouses '10-15-20 year' timeframes for the company, insisting that this is how "we view the company."

In other words, Immelt in effect pleads,

'let's all hail the golden past era of Jack Welch, and please overlook the sub-S&P500 performance over the entire tenure of my CEO- and Chairmanship of GE.'

To see what GE's total return performance has been under Immelt, take a look at the table in this blog post which I wrote earlier today.

Then Immelt plays the 'oughta, shoulda' game. He says that GE stock "should" go up with oil. Darn those stupid investors, eh? Why can't they price his stock right. It's soooo embarrassing!

As if this theatre isn't comic enough, you have to step back and see what CNBC is asking veteran reporters Becky Quick and Joe Kernen to do. They must, with straight faces, lob softballs at their Chairman in a live interview.

Am I the only person who thinks this is ludicrous and demeaning to Quick and Kernen? Does anyone seriously believe either veteran, capable, sane CNBC/GE online anchor will risk her/his career by being candid and hardnosed with their employer's Chairman and CEO on live network TV?

Does anyone seriously believe either will engage in the following hypothetical Q&A?

Quick: Hey, Jeff.....about our total return since you took over from Jack Welch. Why haven't you been able to beat the S&P500 in 4 out of 5 years? And why has our stock underperformed for the period during which you've been CEO?

Immelt: Good point, Becky. I'm recommending to the board today that they fire me and find someone to run the firm who can actually outperform the returns that my shareholders could get from simply buying a passively-managed S&P500 index fund. I can't, in good conscience, recommend that anybody assume the risk inherent in holding GE as a specific equity, when I've failed to return to shareholders what they could get with such an index fund holding.

Kernen: Hey, Jeff.....about this conglomerate we fondly call "GE." With the annual revenues and asset sizes of our disparate and unrelated businesses, don't you think the corporate function is essentially exacting a non-value-adding tax to pay your enormous salary, benefits and bonuses? Wouldn't investors benefit from spinning GE into its five separate businesses, each with its own listed stock, free of the financial yoke of your corporate functions?

Immelt: I'm glad you pointed that out, Joe. Yes, I think you are right. On second thought, I'll recommend to the board that they dismiss me as soon as I've split the firm into its trimmer, more enterprising separate components. I think I've demonstrated, over the five years I've been CEO, that my staff and I have actually destroyed value, not added any, for shareholders. Please help to stop me before I grab even more shareholder value for myself by underperforming the S&P and getting paid many tens of millions of dollars for it.

Quick: Wow, Jeff. Thanks for that breaking news on GE splitting itself up. You heard it first, here, on CNBC. America's Business News Network.

Immelt: Thank you, Becky and Joe. I'm just glad I can finally confess to being unable to create any consistently superior total returns for my shareholders after five years of being paid tens of millions of dollars to attempt the task. Now, I can retire and join Jack Welch in bidding for an old newspaper up Boston way. Nobody expects it to earn good returns for the shareholders, and it'll be a private equity buyout, so there won't really even be a publicly-available total return to worry about- so I think I'll be well-suited to that......

Well, I can dream, can't I? CNBC is more about entertainment than truth or news. This hypothetical exchange will never occur. However, you can vist my prior posts here, here, and here, to read more material supporting the comments in the hypothetical Q&A above.

As I've written before, though, if such an exchange did occur, now.....that would be news. Not to mention real hardball financial business reporting.

It runs about 8+ minutes. However, of particular interest to me was the segment at roughly minute 4:30 into the interview. This is where Joe Kernen of CNBC's Squawk Box program, asks Immelt, his ultimate boss, about why GE, as a conglomerate, is valuable.

Immelt rather brazenly says that GE exists 'because the market lets it exist,' or something like that. You can hear the exact quote for yourself at the video link. In defending the conglomeration, Immelt mentions, "performance" and 'common culture, goals....'

Then, to deflect attention from his own failure as CEO to beat the S&P, he now espouses '10-15-20 year' timeframes for the company, insisting that this is how "we view the company."

In other words, Immelt in effect pleads,

'let's all hail the golden past era of Jack Welch, and please overlook the sub-S&P500 performance over the entire tenure of my CEO- and Chairmanship of GE.'

To see what GE's total return performance has been under Immelt, take a look at the table in this blog post which I wrote earlier today.

Then Immelt plays the 'oughta, shoulda' game. He says that GE stock "should" go up with oil. Darn those stupid investors, eh? Why can't they price his stock right. It's soooo embarrassing!

As if this theatre isn't comic enough, you have to step back and see what CNBC is asking veteran reporters Becky Quick and Joe Kernen to do. They must, with straight faces, lob softballs at their Chairman in a live interview.

Am I the only person who thinks this is ludicrous and demeaning to Quick and Kernen? Does anyone seriously believe either veteran, capable, sane CNBC/GE online anchor will risk her/his career by being candid and hardnosed with their employer's Chairman and CEO on live network TV?

Does anyone seriously believe either will engage in the following hypothetical Q&A?

Quick: Hey, Jeff.....about our total return since you took over from Jack Welch. Why haven't you been able to beat the S&P500 in 4 out of 5 years? And why has our stock underperformed for the period during which you've been CEO?

Immelt: Good point, Becky. I'm recommending to the board today that they fire me and find someone to run the firm who can actually outperform the returns that my shareholders could get from simply buying a passively-managed S&P500 index fund. I can't, in good conscience, recommend that anybody assume the risk inherent in holding GE as a specific equity, when I've failed to return to shareholders what they could get with such an index fund holding.

Kernen: Hey, Jeff.....about this conglomerate we fondly call "GE." With the annual revenues and asset sizes of our disparate and unrelated businesses, don't you think the corporate function is essentially exacting a non-value-adding tax to pay your enormous salary, benefits and bonuses? Wouldn't investors benefit from spinning GE into its five separate businesses, each with its own listed stock, free of the financial yoke of your corporate functions?